In April 2024, the Australian government said it was thinking about banning TikTok in the country. They believed the app was not doing enough to protect the data of young users. At the same time, Ruby, a 17-year-old high school student in Melbourne, opened TikTok to watch videos. She had no idea that the app was collecting information about her likes, location, and even the speed she typed. Like many people, she had never read the privacy policy and could not remember when she clicked “agree.” But did she really have a choice?

In today’s digital world, clicking “I agree” is something we all do without thinking. But is it truly a free decision? If platforms control how we use the internet and collect our personal data, maybe privacy is no longer something we can choose on our own.

The Illusion of Choice: Are We Free to Say No?

Media scholar Terry Flew (2021) explains that big platforms like Facebook and TikTok often say users can control their privacy. But this promise is not always true. Many users do not get real options. They must accept the terms if they want to use the service. Flew calls this a kind of “fake consent” (Flew, 2021).

Platforms also have a lot of power. They control the rules, manage our data, and decide what content we see. They are not neutral. They act as both judge and player. This means they can make the rules and also benefit from them.

From “I Choose” to “I Was Designed”

When we click “agree,” do we really understand what that means?

Nicolas Suzor (2019) points out that platforms write long and hard-to-read policies to protect themselves, not us. In law, we are not seen as citizens with rights. We are just users. That means we don’t get to help write the rules. We just follow them.

Facebook once said it would let users vote on platform policies. But to change a rule, 30% of users had to vote. That meant over 300 million people. Unsurprisingly, the vote failed, even though most people who voted said no. After that, Facebook removed the voting system without saying much. This shows that platforms do not really want to share power (Suzor, 2019).

Welcome to the Platform. Good Luck Saying No.

Platforms like to say that privacy is a matter of choice. But for many users, that choice is designed to be nearly impossible. Media theorist Kari Karppinen (2017) reminds us that treating privacy as an individual responsibility ignores how digital environments are built to discourage refusal. The buttons, default settings, and recommendation systems are not neutral—they are designed to extract as much data as possible.

And it gets worse for those who don’t fit the mold. Studies and leaked documents have shown that platforms like TikTok have downranked or hidden videos from users with disabilities, body differences, or LGBTQ+ identities (Hern, 2019). The rationale? To “prevent bullying.” But in doing so, platforms silence the very voices they claim to protect. It’s a kind of algorithmic discrimination that happens behind the scenes—hard to notice, even harder to challenge.

This shows how consent isn’t just made hard to give—it’s made harder for some. People with fewer digital resources, less legal knowledge, or who belong to marginalized groups are often more vulnerable to privacy loss. The system is not just confusing. It is uneven, opaque, and biased by design.

The TikTok Case in Australia

In 2024, Australia started asking tough questions about TikTok:

- Did the platform explain clearly how it used user data?

- Could users really say no to sharing their information?

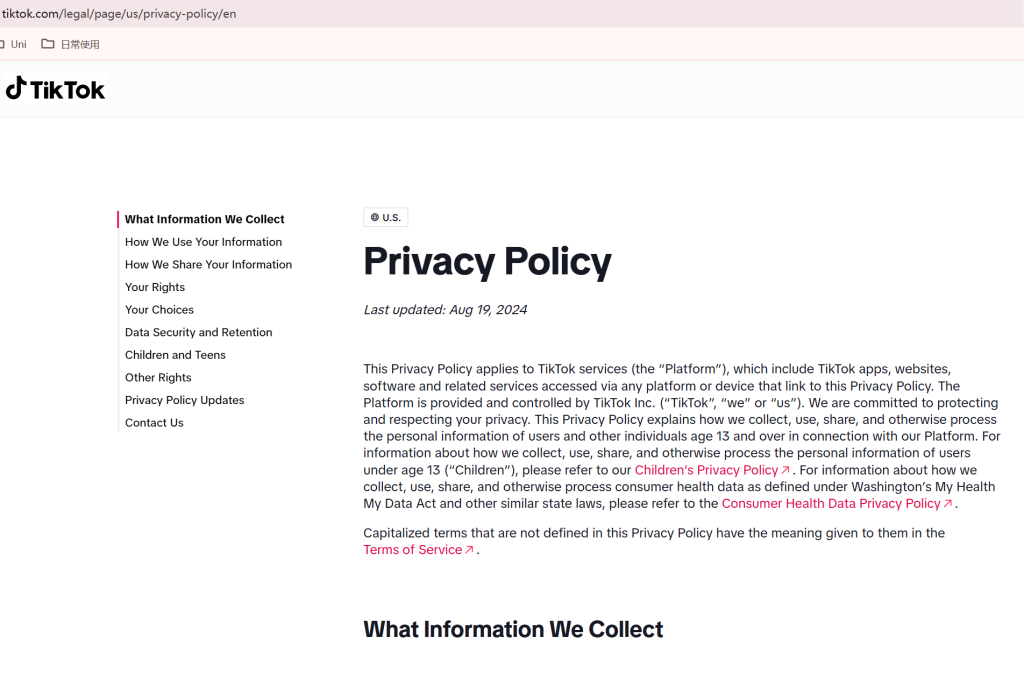

TikTok’s privacy policy was very long and hard to understand. That made it hard for users to make real decisions. Even though TikTok said it was following the law, government officials disagreed. One lawmaker said, “You cannot say users have a choice when you make it so hard for them to say no.”

This event led to new debates in Australia about how platforms should be controlled, as seen in policy responses such as the ACCC inquiry and the News Media Bargaining Code (Flew, 2022)

What Kind of Privacy Do We Need?

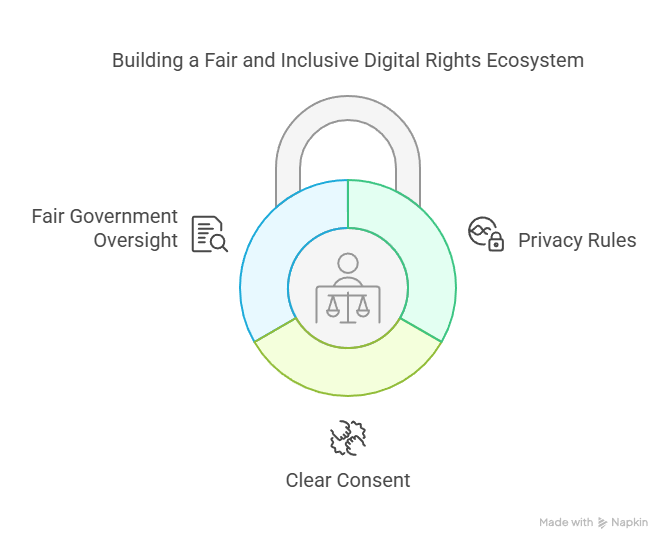

Suzor (2019) says that platform rules are like a digital constitution. But they are written only by companies, not by users or governments. To fix this, we need:

- Regulation: Privacy rules that protect everyone, not just people who read long policies.

- Transparency: Consent that is clear, easy to change, and easy to say no to.

- Responsible Government: Governments that ask: “Is this fair?” instead of just “Did they click agree?”

Karppinen (2017) also says we need to move beyond just freedom of speech. We should care about communication rights, like the right to be heard and the right to control your own information.

What Does “Meaningful Consent” Actually Mean?

The idea of “meaningful consent” is central to global data protection rules like the GDPR in Europe. But what does it really mean? According to the GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation), meaningful consent must be:

- Freely given – The user should not be forced.

- Specific – Consent should be given for a clear reason.

- Informed – The user must understand what they are agreeing to.

- Unambiguous – It must be a clear yes.

- Easy to withdraw – People can change their minds at any time (European Union, 2016).

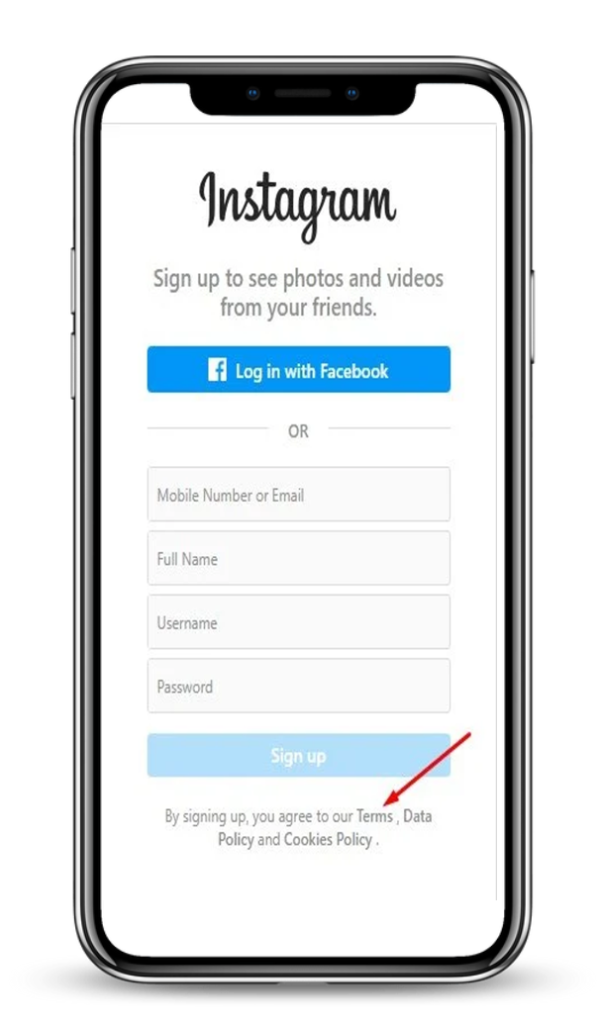

If we compare this to what happens on many social media platforms, we see big problems. When you sign up for Instagram, for example, you must agree to many different policies all at once. There is no clear explanation of each one. You cannot choose what data you want to share. And if you want to stop sharing your data, you often have to delete your account.

A study by Obar and Oeldorf-Hirsch (2020) found that only 1 in 1000 users fully read the privacy policy of a new website. Most people clicked “I agree” within 15 seconds. This shows that the system is not built for understanding or real choice.

Also, many platforms make it hard to find privacy settings. You may need to click through 5 or more pages to turn off targeted ads. And even then, you might still see them.

This design is not a mistake. It is a choice made by companies that benefit from collecting as much data as possible. The harder it is to say no, the more users will say yes without thinking. That is why some experts call current systems a kind of “consent theatre”—where users only appear to give permission, but don’t really understand what’s going on (Nouwens et al., 2020).

So, to protect our privacy, we must demand more than just a checkbox. We need real control, clear language, and the power to say “no” without losing access to basic services.

Why Do Users Ignore Privacy?

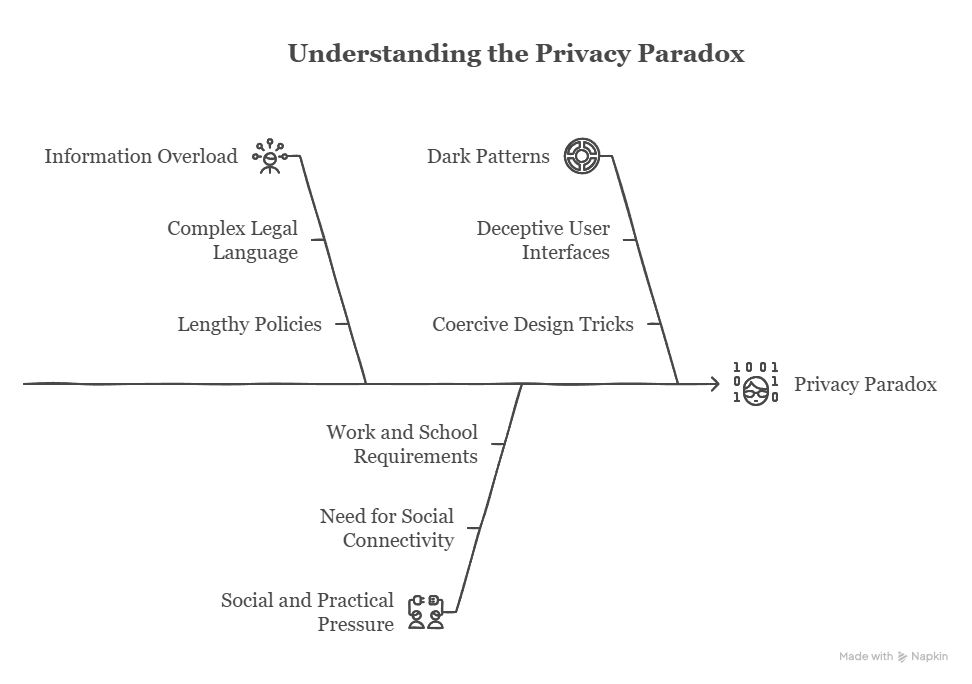

There is a clear paradox in how we think about privacy. In surveys and academic research, people often say privacy is very important to them. A paradox is when two ideas that seem to go together actually conflict. Here, we say we care about privacy, but in practice, we ignore it. In real life, we quickly click “I agree” and move on. We download apps without reading the permissions. We share personal photos, locations, and habits with platforms that we do not fully trust. Why?

Some researchers call this the “privacy paradox.” It shows the gap between what people say and what they do (Kokolakis, 2017). But it would be unfair to say this is only the user’s fault. The truth is more complex and has to do with how digital environments are designed.

First, users face information overload. This means we are given too much information at once. Most privacy policies are long, full of legal words, and hard to understand. Even if we care, it’s not realistic to read every word or understand legal terms. Many people give up because the effort is too high.

Second, we are under social and practical pressure. These are pressures that come from our need to fit in or function in society. We need to use these platforms for school, work, news, and staying in touch. Saying “no” often means missing out on important communication or fun experiences with others.

Third, many platforms use design tricks—called dark patterns—to push people into agreeing. Dark patterns are user interface designs that make it hard to choose privacy. These tricks include small fonts, confusing buttons, or warnings like “this app won’t work unless you accept.” As a result, we give up. Not because we don’t care, but because the system is designed to make resistance hard. Even people who want privacy end up giving it away.

So, the privacy paradox is not a sign of user laziness. It is a signal that the current system is broken. If users are expected to protect themselves, they must be given tools, time, and clear options to do so. These include simple language, shorter policies, and fair default settings. Until then, blaming users only helps the companies that benefit from our confusion.

Conclusion: It’s Not Just You. It Is The System

When Ruby clicked “agree,” she just wanted to watch fun videos. But she also gave away her personal data, without knowing it. She did not write the contract. She did not help make the rules.

Privacy is not simply a matter of ‘personal choice’—it is shaped by structurally manipulative platforms. Through mechanisms disguised as user consent, such as convoluted privacy policies and dark patterns, platforms create an illusion of choice, enabling the systematic extraction of user data. This not only violates individual privacy but also constitutes a structural infringement on digital rights.

In an era when “agreeing” to terms is as easy as a click, we must ask: Is our consent truly ours, or simply a convenient illusion crafted by platforms? This blog has argued that privacy is not a neutral personal choice but a structural issue shaped by opaque policies, manipulative designs, and power asymmetries between users and platforms. As seen in the TikTok case in Australia, even tech-savvy youth like Ruby are largely unaware of how deeply platforms can track, infer, and monetise their behaviours. Scholars such as Flew (2021), Suzor (2019), and Karppinen (2017) have shown how the burden of privacy protection has been unfairly outsourced to individuals under the guise of user choice. But if this “choice” is built on unreadable documents, default settings, and dark patterns, it is no longer a choice—it is a design of control. Recognising this helps us reframe privacy not as a matter of better individual behaviour, but as a call for systemic accountability. If platforms are the new public infrastructure, then privacy should be treated as a collective right, not a checkbox.

References

TikTok. (2024, August 19). Privacy Policy [Screenshot]. TikTok. https://www.tiktok.com/legal/page/us/privacy-policy/en

European Union. (2016). General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). https://gdpr-info.eu/

Flew, T. (2021). Regulating platforms: Communication policy and the media. Polity Press.

Flew, T. (2022). Platforms on trial. InterMedia, 46(2), 24–27. https://www.iicom.org/intermedia/vol-46-issue-2/platforms-on-trial/

Hern, A. (2019, December 3). TikTok owns up to censoring some users’ videos to stop bullying. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2019/dec/03/tiktok-owns-up-to-censoring-some-users-videos-to-stop-bullying

Karppinen, K. (2017). Human rights and the digital. In H. Tumber & S. Waisbord (Eds.), The Routledge companion to media and human rights (pp. 95–103). Routledge.

Kokolakis, S. (2017). Privacy attitudes and privacy behaviour: A review of current research on the privacy paradox phenomenon. Computers & Security, 64, 122–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cose.2015.07.002

Nouwens, M., Liccardi, I., Veale, M., Karger, D., & Kagal, L. (2020). Dark patterns after the GDPR: Scraping consent pop-ups and demonstrating their influence. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1–13). https://doi.org/10.1145/3313831.3376321

Obar, J. A., & Oeldorf-Hirsch, A. (2020). The biggest lie on the internet: Ignoring the privacy policies and terms of service policies of social networking services. Information, Communication & Society, 23(1), 128–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2018.1486870

Suzor, N. (2019). Lawless: The secret rules that govern our digital lives. Cambridge University Press.

Be the first to comment