Invisible referees and decision makers: how AI is taming our attention when algorithms start governing society.

It seems that we are always blinded by a layer of cloth called algorithmic data, and our attention is confined to a small wall of information.

When you swipe Netflix, the movies recommended by the system will always match your taste; when you open the map to look for a place for dinner, the top of the page will always show the chain restaurants that are “highly rated and close to you”; when you open a news app, you will see the topics that you “might be interested in” – sports, entertainment, life tips…. You open a news app and see all the topics you’re “likely to be interested in” – sports, entertainment, life hacks. You almost forget about wars, elections or social protests because they don’t “fit your interest profile”.

In the platform dominated information space, algorithms are not only predicting our behavior, they are building the content we can see. It decides which information appears on the front page, which comments are amplified, and which opinions are hidden. It is like an invisible referee, replacing institutional rules with precise calculations, and shaping the space of public opinion with recommendation logic and clicks. Under the platform logic, algorithms decide whether news is “worth seeing” based on user behavioral data, engagement, click-through rates, and other factors (Brown et al., 2022).

Is it really a so called coincidence? Or is the algorithm making the decision for you

You may think it’s accidental, a ‘convenience’ of big data, that you’re actively ‘choosing’, but it’s backed up by a complex and vast system, from content recommendations, to job screening, to risk scoring, artificial intelligence (AI) and automated systems have AI and automated systems have silently infiltrated every aspect of our daily lives. You think you’re choosing, but you’re just accepting a set of pre-calculated results; the reality you think you’re seeing is no longer a complete reality, but a version that’s been “screened and optimized” by the platform. In this seemingly free, but highly programmed environment, do we still have the real “right to information choice”?

As Just and Latzer (2019) suggest, modern society has transitioned from “government governance” to “algorithmic governance”. Using algorithms as a tool, platforms have begun to quietly play the role of content filters, behavioral regulators, and reality constructors. This “governance power” is hidden in the code and recommendation logic, making algorithms not only a tool, but also an invisible form of power.

Algorithms are not neutral technologies but extensions of power structures: from constructing reality to dominating it.

Algorithms are usually perceived as a ‘technology-neutral’ means of decision-making, free of bias and preference. But the truth is that algorithms operate under a certain logic and goals that do not stand in for fairness and diversity, but rather ‘eyeballs’ and ‘click-throughs’ to increase the platform’s revenue.

Just as platform algorithms do not passively present information, but actively select, sort, amplify, and silence information to build the way people understand the world (Just & Latzer, 2019)

An example of gender bias is in Google Translate, which has caused controversy by translating ‘doctor’ as male and ‘nurse’ as female. Since Translate’s translation model is trained on a large bilingual corpus, it is based on the preferences of past language speakers, cultural stereotypes of gender roles, and the symbiotic relationship between the frequency of occupations, personalities, and genders.

Prates, Avelar & Lamb (2020) tested 12 gender-neutral languages:

When tested on 50 occupational titles, more than 44% of occupations were male by default; For example, words such as “engineer,” “scientist,” and “president” were translated as “he” in over 90% of cases. “he”; For words such as “teacher”, “nurse” and “librarian”, 80% were translated as “she”.

Google Translate’s gender bias problem is a good illustration of the fact that algorithms don’t create stereotypes, they just ‘translate’ the inequalities of society into ‘gender biases’. It simply “translates” social inequalities into seemingly natural linguistic structures. To the user, “he is a doctor” is a reasonable prediction, but behind the technology is the ‘statistical’ dominance of gender roles in past data.

Algorithms are never neutral; they not only tell us “what to look at” but also quietly decide “what is worth looking at”.

As Noble (2018) and Just & Latzer (2019) point out: platform technologies are “selectively constructing reality” rather than neutrally presenting it. In other words, it doesn’t just construct reality pushing things in front of our eyes it dictates reality making us believe that these things are “all reality”. Behind these behaviors may be gender roles, cultural biases, consumer preferences, etc. When these are fed into the system and repeated over and over again, the algorithm becomes a kind of “invisible rule maker,” inadvertently defining what is important”, what is ‘mainstream’, ‘whose voice should be heard’. Algorithms have gone from being what we used to think of as “data tools” to a new governance mechanism: a system that determines visibility, participation, and valorization, that asserts power through computation, and that defines reality through code.

How AI systems are taming our attention?

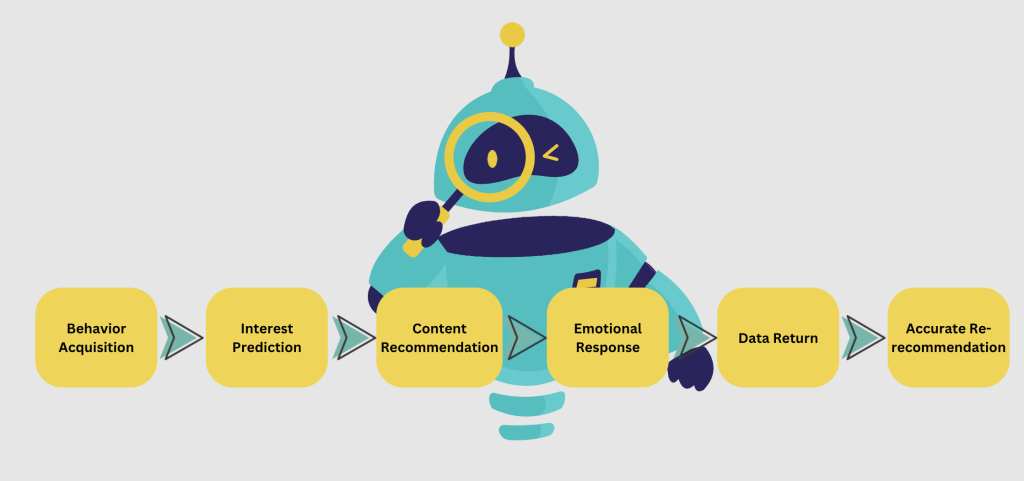

The goal of the platform and the Ai system is not to help you gain more knowledge or diversity of information, but to maximize the user’s length of stay and click interactions, the AI is not trying to “satisfy your interest”, but to cultivate an interest that can be easily controlled by it.

Behavioral mechanisms for domesticating attention:

This mechanism was first formed in Netflix, Facebook, YouTube and other platforms, and has since been widely used in short videos, social media, news, and search engines. It records not only what you watched, but also in which image you stayed longer? Which titles and contents make you emotionally intense? What style of video do you play over and over again?

This cycle forms an “attention cocoon”, so that in the seemingly “free choice”, we increasingly only see content that agrees with our own views and strong emotions.

“Human future behavior itself has become a commodity for AI platforms.” -(Zuboff, 2019)

“Predicting what you’re going to do next” is the core business logic of the platform, and all algorithms serve to predict and shape behavior(Zuboff, 2019).

For example, in a famous experiment conducted by Facebook in 2014, Emotion Manipulation and Behavioral Prediction of Users, researchers experimentally tweaked the content of news pushes for 689,003 Facebook users and found in a subsequent study that negative words in their follow up statuses increased when users saw less positive content, and positive words in their statuses increased when they saw less negative content, and an increase in positive words in their statuses when they saw less negative content (Kramer et al., 2014). This suggests that platforms are using AI to govern emotions and behaviors, and this experiment shows how AI not only predicts behavior, but also actively shapes behavior and emotions – completing the “domestication” of attention.

The Netflix documentary “The Social Dilemma” also sheds light on this phenomenon.

Image fromThesocialdilemma.com

The documentary delves into how social media platforms are using AI technology to manipulate user behavior, especially the behavioral patterns and emotional responses of teenage users, and how algorithms are driving the spread of disinformation. Together, these examples reveal a core mechanism: AI systems are domesticating human attention into a resource that platforms can sustainably leverage and cash in on by predicting and manipulating behavior. We often think of AI as some kind of high-tech “floating in the cloud” that operates on its own algorithms, but this is not the case at all; AI is not an intelligent machine divorced from reality, it is not neutral, and it is all related to real-life power relations. As Crawford (2021) puts it: AI is “deeply rooted in the real world” and is not just a technology, but a product of social, political and economic rules.

The algorithm is the referee, but we haven’t even read the rules:

Algorithms have been integrated into our lives. From recommendations on social platforms, screening on job search platforms, to hobbies and interests, and public safety monitoring, almost every decision is more or less intervened by algorithms. But the problem is that we know almost nothing about these systems. As Frank Pasquale (2015) pointed out in The Black Box Society, many of the algorithmic systems we rely on today are actually operating in an “invisible black box.” These systems neither disclose their operating logic nor accept external supervision, but quietly make a large number of decisions that are closely related to our lives. They have become “invisible decision makers” who decide what content can be seen by people without supervision, review, and democracy.

The power structure behind algorithmic logic:

What we need to pay attention to is not only whether the algorithm will make mistakes, but who sets its goals? Whose standards does it use to judge what content is important? These questions are what really affect us. The algorithm will constantly adjust the content push based on your click behavior and historical data to “tame” you. The world you see is “tailored” step by step based on your past clicks, interactions, and browsing records. And those voices that are not so easy to click, calm opinions, and topics that are in-depth but not eye-catching enough are slowly marginalized. The goal of the algorithm should not be just to “let you watch for one more minute”, but to respect your right to choose, freedom of information, and ability to understand the world.

If algorithms have become “invisible referees”, how do we respond to the domestication of attention by AI systems?

This is the core concern of AI governance: we can no longer see algorithms as mere technological tools, but as part of social governance.

Algorithmic transparency: We have the right to know “why I saw this content and not another”.

Accountability of AI systems and algorithms: AI systems must be subject to the same regulatory scrutiny as finance, healthcare, etc., especially when it affects our access to education, our mindset, our hiring outcomes, and even our perception of the world.

Mechanisms for public participation: algorithmic governance should not be left to the discretion of technology companies or government rights alone; the voices of ordinary users should also be heard and embraced.

AI that is truly beneficial to us is not something that we can become addicted to and passively accept, but something that helps us better understand the world and make our own judgments.

We don’t want smarter AI, we want a fairer system:So what we should be looking at is not “are we being manipulated by algorithms”, but “how are these algorithms designed? Who decides how they’re going to work? Who are these systems helping and who are they excluding?” It can’t just be a desperate attempt to grab our attention, it has to be accountable to everyone. It has to be visible and accountable, not a mysterious program hidden in a black box.

As important as AI advances are, the way it is governed is just as important. If a system is powerful enough but no one can manage it, it can be harmful to society. Our goal is not to make machines more and more “intelligent”, but to ensure that everyone can still have basic rights – such as the freedom of choice, expression and voice – in this smart society.

To do this, we need to re-establish a relationship where “people call the shots” rather than “algorithms call the shots”. It may not be easy, but it is the beginning of taking back control of our attention and choices.

It’s not technology that determines society, it’s us that determine how technology is used.

Brown, M., Nagler, J., Bisbee, J., Lai, A., & Tucker, J. (2022, October 13). Echo chambers, rabbit holes, and ideological bias: How YouTube recommends content to real users. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/echo-chambers-rabbit-holes-and-ideological-bias-how-youtube-recommends-content-to-real-users/

Crawford, K. (2021). Atlas of AI: Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence (pp. 1–21). Yale University Press.

Flew, T. (2021). Regulating Platforms. John Wiley & Sons.

Kramer, A. D. I., Guillory, J. E., & Hancock, J. T. (2014). Experimental evidence of massive-scale emotional contagion through social networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(24), 8788–8790. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1320040111

Meese, J., & Bannerman, S. (2022). The Algorithmic Distribution of News. Springer Nature.

Salzberg, A. (2021, April 12). The truth behind Google Translate’s sexism. Aiatranslations.com; aiaTranslations LLC. https://aiatranslations.com/blog/post/the-truth-behind-google-translate-s-sexism

Zuboff, S. (2019). The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: the Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. Public Affairs.

Be the first to comment