—- A case study on The Voice of April reveals the power of data behind algorithmic censorship

Part 1: Hearing The Voice of April – Do We Really Hear It?

On April 22, 2022, a six-minute video titled “The Voice of April” went viral on social media platforms in China. The video is devoid of any dramatic scenes – there are no arguments or conflicts – and consists solely of real audio clips recorded in Shanghai during the city’s lockdown. The video features over twenty audio clips from Shanghai residents, quarantine personnel and government officials, paired with drone footage of the city presented in black-and-white tones (Yang, 2022). It highlights the critical moments during the Shanghai blockade, both the positive events of residents helping each other to persevere and the more disheartening situations arising from ineffective quarantine measures (Yang, 2022).

The video shows a woman pleading for medical assistance for her feverish child, a resident taken to a quarantine site complaining about the rudimentary facilities and lack of basic supplies, and a pet owner shocked that his dog was taken away by quarantine personnel (Kevin in Shanghai, 2022). These authentic voices quickly resonated with the public but were deleted from major social media platforms soon after.

Who decides the fate of these voices? Is it human censorship or a more insidious force – algorithms? By exploring this incident, we will reveal the profound threat that algorithmic censorship poses to public freedom of expression and the governance of online platforms. This situation reveals that automated censorship mechanisms increasingly control public discourse while authentic voices and collective memories are silently erased.

Part 2: The ‘Black Box’ of Algorithmic Censorship – Invisible Political Manipulation

To understand the fate of The Voice of April, we first need to understand the phenomenon of the ‘black box’ of algorithmic governance. As Frank Pasquale discusses in The Black Box Society (2015), where digital platforms often use opaque algorithmic mechanisms to review and make decisions about content. Such mechanisms are challenging to trace and hold accountable (Frank, 2015). A prime example of such opaque decision-making is the rapid removal of The Voice of April: the public has no clear understanding of which rules were allegedly violated, only witnessing the platform’s swift and repeated takedown of the video.

In China’s online platforms, algorithmic censorship frequently relies on keywords, images, and even voice features for automatic identification. The Voice of April had garnered over 5 million views before it was removed (Yang, 2022). As the video was censored, copies were re-uploaded and rebroadcast by the public. However, on the night of the original video’s release, each version and comment supporting the content were almost immediately removed (Yang, 2022). While the public lacks concrete evidence to confirm that algorithms drove the video’s deletion, the near-simultaneous content blocking is concerning.

The nature of algorithmic censorship is not a purely technical operation but rather reflects how political power structures operate covertly through digital technology. This technical behaviour reflects the “power dynamics” of algorithmic governance, where power is exerted under the guise of algorithms (Frank, 2015). This not only circumvents the responsibility of human judgment, but also enhances the efficiency and covertness of information suppression (Frank, 2015). Through such censorship, power institutions are able to efficiently control the flow of information, thus stabilizing and reinforcing their own positions of authority (Frank, 2015). Just and Latzer (2016) point out that algorithms not only filter content but also reshape collective consciousness and social order (Just & Latzer, 2016). The ability to manipulate algorithms translates to the power to influence social dynamics, affecting social interactions and public discourse. This manipulation can exacerbate social inequality and undermine democratic principles (Frank, 2015). The significance of the deletion of “The Voice of April” lies not in the video’s content, but in how power uses algorithms to redefine public perceptions and memories.

Part 3: The Dual Role of Platforms – The Publisher and Gatekeeper in Conflict

When we further trace the power behind the algorithms, we discover that the platforms occupy a contradictory position. Digital platforms operate with a dual role of public discussion and private censorship. On the one hand, Chinese digital platforms such as WeChat and Weibo function as content facilitators by using algorithms to manage and distribute vast amounts of user-generated content (Terry, 2021). This operation promotes the democratization of information and supports creative diversity. On the other hand, these platforms also act as gatekeepers of information. Their algorithmic decisions can unwittingly insulate them from responsibility for the consequences of censorship (Terry, 2021). By relying on automated systems, these platforms treat content decisions as processes generated by algorithms, allowing them to deflect responsibility for the outcomes of those decisions (Terry, 2021). Furthermore, Kate Crawford (2021) describes algorithms as a tool for travelling power and resource distribution mechanisms in “The Atlas of AI: Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence”. Specifically, when platforms deploy algorithms, they engage in a political act closely aligned with government interests (Crawford, 2021).

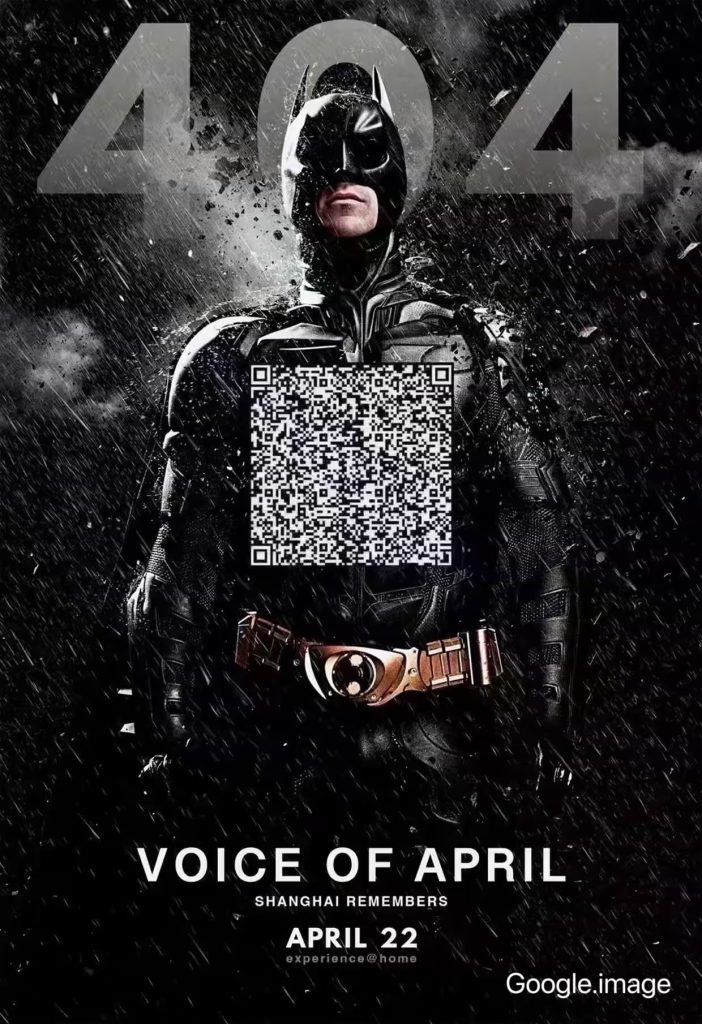

However, this powerful algorithmic control has sparked a public creative revolt. The original creator retained a copy of the video and stored it on a cloud drive while “The Voice of April” was being censored (Yang, 2022). When the video began to be removed, the public found ways to preserve and share it, such as creating memes, hiding QR codes, placing the original audio in clips of popular movies and television shows, or even utilizing blockchain technology (Yang, 2022). This innovative form of resistance highlights the public’s awakening and strategic opposition to algorithmic power structures.

Part 4: The Algorithmic public spaces – Whose Voice Deserves to be Heard?

The public revolt prompts us to reconsider whose voice is actually heard in a public sphere dominated by algorithms. Indeed, algorithms do not simply enforce neutral directives. They operate within existing social structures and historical biases (Noble, 2018). Moreover, algorithms are not passive tools for filtering content but rather mechanisms for actively shaping the public sphere, influencing our perceptions of which ideas are “worth hearing” (Noble, 2018). As a result, “The Voice of April” is not only censored but the expression and visibility of a collective experience are erased from the public view.

Safiya Umoja Noble (2018), in her book” Algorithms of Oppression: how search engines reinforce racism”, simultaneously criticizes the fact that algorithmic systems, influenced by the values and prejudices of their creators, consistently reinforce dominant power structures while silencing the voices of minority or marginalized groups (Noble, 2018). “The Voice of April” strikes at the key of this issue: the power of video lies not in revealing new facts, but in uniting fragments of emotion from the daily experiences of countless individuals. This creates a collective echo that cannot be ignored. Just two days after the release of the video, both The Guardian and the BBC reported on the real-life shortage of supplies and the strain on medical resources during the lockdown in Shanghai (Ni, 2022; BBC, 2022). Official reports from foreign mainstream media also confirmed the authenticity of the video’s content.

This algorithmic censorship mechanism has significantly impacted the inclusiveness and fairness of digital public space over time. In the case of “The Voice of April”, the urgent voices of Shanghai residents were marginalized, and the recordings and expressions of ordinary individuals were excluded from the algorithmically defined “safe space” (Noble, 2018). This situation deprived them of their right to speak out. Therefore, existing inequalities and social divides were further reinforced. It is essential to implement governance mechanisms that ensure public spaces are genuinely open and inclusive to prevent algorithmic bias and undue concentration of power from undermining public authority and social justice.

Part 5: The Future of Algorithmic Governance – Public Participation and Transparency

“The Voice of April” incident is not an isolated case. It highlights how technology is shaping our freedom of expression. Social media platforms across the globe, including TikTok and Meta’s platforms, face similar challenges related to censorship. When an algorithm determines what constitutes “acceptable speech,” it raises the question: who defines an “acceptable algorithm”?

When “The Voice of April” is consistently removed, the issue extends beyond just the disappearance of a video. It uncovers the deliberate suppression of specific social emotions and collective memories. The video shows the authentic voices of people in crisis, which articulate emotions and questions that often challenge the stability of the narratives favoured by those in power. As a result, these voices become targets for filtering and suppression by platform systems. Algorithms have become a primary tool because they can obscure the value judgments and ideological biases embedded within them, presenting a facade of “technological neutrality” (Frank, 2015; Crawford, 2021). In this sense, algorithms are not merely instruments of governance but embody modern political control techniques (Frank, 2015; Crawford, 2021; Just & Latzer, 2016).

Therefore, we cannot solely focus on the “standards” of algorithmic governance; we need to confront the hidden power structures behind it. The future direction of governance should prioritize the establishment of institutional responsibility and the guarantee of public participation. Platforms should no longer use the complexity of the technology as an excuse to avoid public scrutiny. The public has the right to discuss who should manage these technologies and how to make them more equitable.

We need to collaborate and engage critically with technology to ensure that algorithms do not perpetuate existing inequalities but instead promote fairness and inclusiveness in public spaces (Noble, 2018). Specific policy reforms could include implementing transparency mechanisms for algorithmic reviews, with clear disclosure of review criteria and decision-making processes, and promoting citizen engagement through monitoring and feedback channels. This would empower the public to challenge any unfairness in algorithmic decision-making. In addition, establishing an independent third-party regulator is essential for ensuring clarity in responsibility and maintaining checks and balances in algorithmic governance.

While “The Voice of April” may have faced deletion many times, its echoes cannot be entirely erased. Each retweet and discussion challenges the logic of algorithmic domination and a concrete expression of the public’s insistence on the right to be heard. The public’s “voice” is a force that no technological system can completely suppress.

References

BBC. (2022, April 24). Shanghai: Censors try to block video about lockdown conditions. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-61202603

Crawford, K. (2021). The Atlas of AI: Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence. Yale University Press.

Frank, P. (2015). Introduction – The Need to Know. In The black box society : the secret algorithms that control money and information (pp. 1–18). Harvard University Press.

Just, N., & Latzer, M. (2016). Governance by algorithms: reality construction by algorithmic selection on the Internet. Media, Culture & Society, 39(2), 238–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443716643157

Kevin in Shanghai. (2022, April 23). The Voice of April — Voice from Shanghai Lockdown. YouTube. https://youtu.be/38_thLXNHY8?si=rcni1iRTvwoIVBZC

Ni, V. (2022, April 22). Shanghai: video maker urges people to stop sharing film critical of Covid lockdown. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/apr/22/sound-of-april-chinese-netizens-get-creative-to-keep-censored-film-in-circulation

Noble, S. U. (2018). A Society, Searching. In Algorithms of oppression : how search engines reinforce racism (pp. 15–63). New York University Press.

Terry, F. (2021). Issues of Concern. In Regulating platforms (pp. 79–86).

Yang, Z. (2022, April 22). WeChat wants people to use its video platform. So they did, for digital protests. MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/2022/04/24/1051073/wechat-shanghai-lockdown-protest-video-the-voice-of-april/

Be the first to comment