“You nailed the interview. Or so you thought — until the AI said no.”

Welcome to the age of algorithmic hiring, where machines, not humans, may decide your professional future.

As artificial intelligence (AI) technologies rapidly reshape recruitment practices, companies are increasingly relying on automated systems to screen resumes, analyze interviews, and predict candidate success. From an efficiency aspect, AI is playing an increasingly important role in recruitment worldwide.

However, while AI promises efficiency, consistency, and scalability, its application in recruitment raises serious ethical concerns. These include the erosion of privacy, lack of transparency, and the risk of perpetuating existing social biases through algorithmic decision-making. Sensitive data like job applicant’s social media profiles and personal history is processed by many AI recruitment tools without the full knowledge or consent of the applicant. The fact that there is no transparency regarding how data is used and shared is a very dangerous thing to personal privacy. In addition, we do not assume that algorithms should be free from algorithmic bias. Algorithms try to predict behavior with historical data, and thus might be designed to reproduce any pre-existing social biases.

AI in Recruitment: The Promise and the Pitfalls

AI is transforming how companies identify, assess, and hire candidates. For decades, human recruiters manually reviewed piles of resumes—a time-consuming and often subjective process. An alternative that allows for more efficient application of AI—modern automated systems capable of assessing thousands of pieces of data to find the best possible candidates. AI driven recruitment tools make use of the algorithms which assess various aspects such as skills, experience, culture fit, making it much faster than the manual process. Automated tools now scan thousands of resumes in seconds, conduct one-way video interviews, and evaluate candidates based on speech patterns, facial expressions, and language use. In theory, these tools eliminate human bias and increase objectivity.

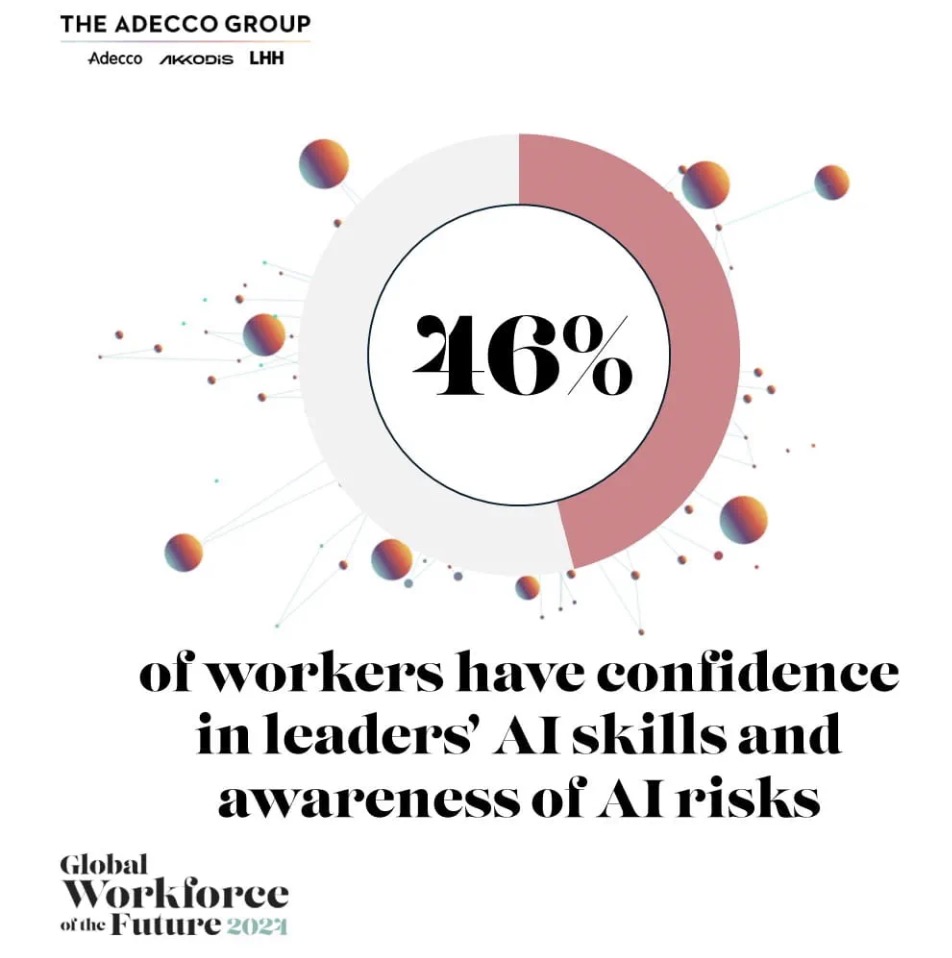

Showed in the Adecco Group’s Working Through Change: Adapting to an AI-Driven World of Work 2024 report, 23% of workers have been trained on how to use AI at work, and 46% of workers have confidence in leaders’ AI skills and awareness of AI risks.

But behind the promise lies a troubling reality. Privacy is the most pressing concern. Typically, the data that is used for these AI recruitment tools includes vast amounts of personal data. It may include resumes and application forms, but can also include data pertaining to candidates and their social media profiles, online behavior and to some extent psychological information. However, this kind of data collection often occurs without proper user consent, raising serious privacy concerns. This leads to a situation where candidates’ personal lives are dissected to the greatest extent that recruitment methods of the past never permitted. They do not even know that their online activities are being scrutinized to determine their suitability for a job.

It is a lack of transparency which leads to the central questions about informed consent. What should companies do with personal data when using it to decide to hire someone that may, in turn, affect his or her employability? No matter how much data candidates provide, they are essentially left on their own to the decisions made with partial or distorted data. As AI tools muscle their way into the recruitment scene, transparency and consent in the usage of those tools’ data are crucial when it comes to protecting applicants’ privacy, as well as maintaining fairness (Zuboff, 2019; Müller, 2020).

Invisible Filters: Gender and Race Bias in Algorithmic

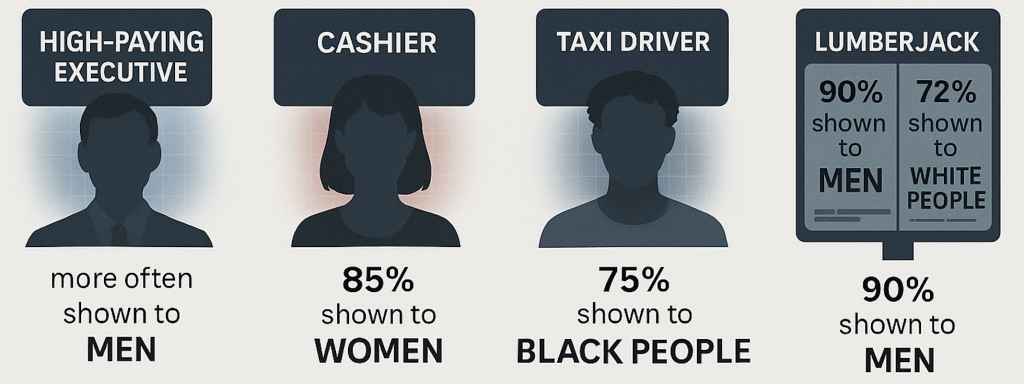

Despite being more efficient and objective in recruitment, bias and discrimination can also be subtly embedded within algorithmic systems, quietly undermining fairness in hiring processes. Algorithmic recruitment bias is not limited to resume screening—it also shapes who sees which job ads.

In a study by Carnegie Mellon University, Amit Datta and colleagues used an automated tool called AdFisher to examine Google’s ad delivery. They discovered that men were significantly more likely than women to be shown ads for high-paying executive roles, even when browsing behaviors were identical (Datta et al., 2015). A 2019 U.S. study further revealed how Facebook’s ad optimization system distributes employment ads in biased ways. Despite having the same target audience set by advertisers, ads for cashier roles were delivered to 85% women, while taxi driver jobs were shown to 75% Black users, and lumberjack positions to 90% men and 72% white users (Ali et al., 2019). These skewed outcomes result not from explicit targeting, but from algorithms trained to maximize click-through rates—often replicating societal stereotypes in the process.

Similar trends appear in China, where platforms like Zhilian, BOSS Zhipin, and Liepin show gendered patterns in resume visibility. Searches for jobs like Programmer tend to favor male candidates, while Receptionist results prioritize female profiles. These invisible algorithmic filters risk reinforcing discrimination under the guise of optimization.

In traditional hiring, job seekers are already in a weaker position. AI recruitment makes this worse by giving them no way to challenge unfair results. Whether someone gets hired, how much they are paid, and what future jobs they can get—all of these are affected by decisions they cannot see or control.

HireVue’s Video Interviewing Technology

HireVue, a leading AI recruitment platform, has faced criticism for its use of facial analysis and voice recognition to assess job candidates. Using AI, the platform scores candidates for a role based on how facial expressions, voice patterns and other variables during a video interview assess that candidate’s suitability. However, this system aims at efficiency and minimizing the human bias, which has raised a lot of concerns regarding transparency, as well as the possibility of discriminatory results.

Also, HireVue’s AI system is not transparent at all about how it works. Generally the AI selects candidates by criteria that candidates are unfamiliar with and that they are unable to challenge or understand the basis for the system’s decisions. This focuses the AI on cues that may skew towards some demographics. For example, if a behavior has high affinity for expectations for confidence and competence in a candidate, then that statement will be rated more favorably. This is biased against individuals not fitting into these kinds of behavior, for example when introverts or people from other cultural backgrounds speak differently.

Storage and use of data is another big issue because of which many countries have imposed tariffs on cross border data sharing. In many cases, candidates do not control the storage, processing, or sharing of their video data. This is a privacy issue, particularly in the case of a video interview which often contains some sensitive personal data. The related issue of informed consent is also of great importance. Müller (2020) notes that candidates might not be fully aware of what implications they have on their facial expressions and voice patterns, so the ethical piece of using this technology during the recruitment process becomes even complicated.

Amazon’s Gender-Bias Problem

The Amazon’s AI recruitment tool in 2018 is a well-known case of the privacy and governance issues in AI recruitment. To make resume review a process that is automated, Amazon built an AI system that helps decide applicants based on their qualifications, skill sets and experience. However, the tool turned against female candidates. The reason this occurred is because the system was trained on data containing many male history, making it a male-biased system. Thus, the algorithm developed a preference for resumes containing male associated language and skills, even if these factors did not relate to the job selection.

Amazon’s goal of eliminating human bias from the hiring process is undermined by this gender bias in the company’s AI recruitment tool. Unintentionally, the algorithm gave preference to language or traits that are associated with male applicants, and thereby reinforced already existing disparities by the gender. The larger issue raised in this case showcases what algorithmic governance actually means: even algorithm that are purported to be neutral, consequentially reinforce and even exacerbate existing social biases. These algorithms also control the decision making processes and hence they affect real lives and determine career opportunities in a way that may be unfair or discriminatory (Binns, 2018).

Finally, Amazon’s case brings into question major ethical standards. Who does a responsibility to fix the system when an AI system perpetuates the biases? Should algorithms have discriminatory impact taken out of their hands and human beings made accountable for them? Fairness is about how these algorithms work for almost all decisions. Without accountability, AI systems can reproduce inequalities and are in fact the very opposite to AI’s promise to provide a fairer, more efficient way of hiring.

Algorithmic Governance: The Challenge of Fairness and Accountability

Algorithmic governance is the concept of the growing influence of algorithms in determining our lives, from choices in employment, law enforcement, as well as judicial decisions. The rise of algorithmic governance in recruitment highlights the need for ethical oversight. When algorithms mediate access to economic opportunities, their fairness must be scrutinized. As the HireVue and Amazon cases show, AI systems can produce biased and opaque outcomes that have tangible effects on people’s lives.

Numerous studies have shown that facial recognition algorithms tend to have significantly higher error rates for women and people of color, especially Black women. For example, Buolamwini and Gebru (2018) found that commercial gender classification systems had error rates as high as 34.7% for darker-skinned women compared to less than 1% for lighter-skinned men. This disparity is not just technical—it becomes discriminatory when used in hiring contexts, where it may unfairly penalize candidates based on race or gender.

Further, Raji and Buolamwini (2019) demonstrated how public auditing of these systems reveals persistent disparities in accuracy and fairness. These findings illustrate that flawed or incomplete training data can result in systemic exclusion, often without the affected individuals ever knowing it.

To address these issues, several principles must be adopted:

- Transparency: Candidates should know when AI is being used, what data is collected, and how decisions are made.

- Explainability: Algorithms must be interpretable, with clear reasoning behind outcomes.

- Fairness Audits: Independent audits should assess systems for bias and disparate impact.

- Consent and Control: Data collection must be voluntary, with clear options to opt in or out.

- Human Oversight: Final hiring decisions should involve human judgment, not rely solely on machines.

Conclusion: Confronting the Hidden Harms of AI Recruitment

AI recruitment is advantageous in that it’s more efficient, data driven and there is a possibility to limit human biases. There are many concerns surrounding these benefits—namely privateness, algorithms governance, fairness—but nonetheless these are benefits. Given the use of AI changing the landscape of the recruitment, it is necessary to tackle these issues to make sure of AI responsible and ethical use.

The biggest issue is that personal data of candidates should be protected. If the process of collecting, using and storing applicants’ data is not transparent with companies then it shouldn’t be. This allows the consent to be informed, and the candidates to understand how the data supplied by them is being used.

Furthermore, the bias in algorithm needs to be mitigated. To avoid continuing to perpetuate existing societal inequalities for all the world, these AI recruitment tools need to be regularly audited for fairness too. In order to have fair hiring practices, it is important to build transparency in the algorithmic decision and also to hold accountable for the decisions.

With AI recruitment, policymakers are responsible for setting up the regulations that preserve people’s rights and ensure justice in the recruitment process. Issues with these areas can be addressed to take full advantage of what AI offers in simplifying the recruitment process while maintaining privacy, fairness, accountability, etc., in the hiring process.

References

Binns, R. (2018). Fairness in machine learning: Lessons from political philosophy. Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Fairness, Accountability and Transparency, 149–159. https://doi.org/10.1145/3287560.3287591

Buolamwini, J., & Gebru, T. (2018). Gender shades: Intersectional accuracy disparities in commercial gender classification. Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, 81, 1–15. https://proceedings.mlr.press/v81/buolamwini18a.html

Crawford, Kate (2021) The Atlas of AI: Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1-21.

Flew, Terry (2021) Regulating Platforms. Cambridge: Polity.

Jin, L., Radko Mesiar, & Qian, G. (2018). Weighting Models to Generate Weights and Capacities in Multicriteria Group Decision Making. IEEE Transactions on Fuzzy Systems, 26(4), 2225–2236. https://doi.org/10.1109/tfuzz.2017.2769041

Müller, V. C. (2020, April 30). Ethics of Artificial Intelligence and Robotics. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy; Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

Nissenbaum, H. (2010). Privacy in context: Technology, policy, and the integrity of social life. Stanford University Press.

Noble, S. U. (2018). Algorithms of oppression: How search engines reinforce racism. NYU Press.

O’Neil, C. (2016). Weapons of math destruction: How big data increases inequality and threatens democracy. Crown Publishing.

Raji, I. D., & Buolamwini, J. (2019). Actionable auditing: Investigating the impact of publicly naming biased performance results of commercial AI products. Proceedings of the 2019 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, 429–435. https://doi.org/10.1145/3306618.3314244

Suzor, Nicolas P. (2019). ‘Who Makes the Rules?’. In Lawless: the secret rules that govern our lives. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. 10-24.

Zuboff, S. (2019). The age of surveillance capitalism: The fight for a human future at the new frontier of power. PublicAffairs.

Be the first to comment