We live in a world of algorithms, that govern almost everyone’s online activities. China has the largest food delivery market in the world. There are more than 450 million people ordering food online, with more than 56,000 orders generated every minute (China Daily, 2025). As a pillar industry of China’s platform economy, the food delivery industry is currently worth more than 200 billion US dollars (CNN, 2024).

However, everything came with a price. Behind the convenient online delivery industry that Chinese people are proud of, there are more than 10 million food delivery workers, Chinese people often call them “the riders” (Figure 1, China Daily, 2025).

Algorithms are a dual-edged sword. While they bring unprecedented convenience to people, they also monitor their moves all the time.

The riders maximize the use of algorithms, or rather, are exploited by algorithms. Their cooperation or confrontation with algorithms can be said to be the best example of algorithmic governance and surveillance capitalism.

The rise of the food delivery empire

Meituan, founded in 2008, the largest online delivery platform in China, was the enabler of the delivery algorithms. In 2024, Meituan reached 60.7 billion yuan in revenue, with an operating profit of billion yuan, its profits far exceed those of traditional catering enterprises in Beijing, which has been declining for years (Zhang, 2025).

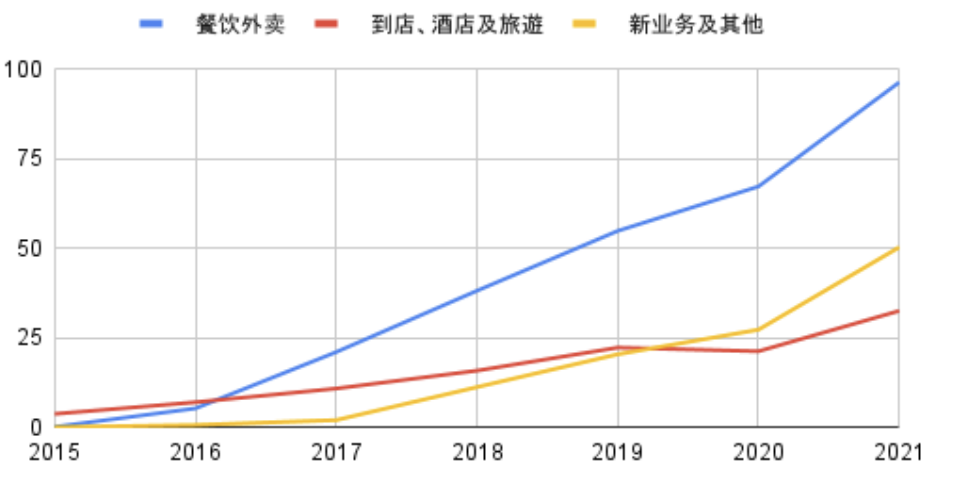

However, it was not until 2016 that Meituan made its food delivery business its main source of profit, and from that year onwards, the revenue from its food delivery business completely exceeded that of the company’s other businesses (Figure 2, CLB, 2023).

Blue line: food delivery

Red line: in-person dining, hotel, and tourism

Yellow line: new business and others

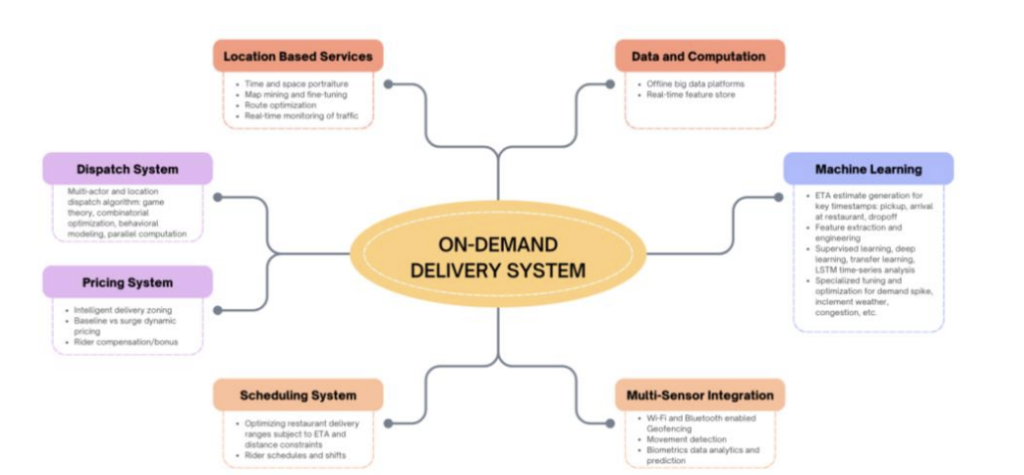

All this is thanks to the “Super Brain” delivery system launched by Meituan in 2016-2017. In short, this is an algorithm that optimizes delivery efficiency based on collecting various data, to allow delivery riders to deliver orders to customers accurately in the shortest time possible (Zhang, 2025).

Working under algorithms governance

Before the age of algorithms, food delivery platforms relied on dispatchers or the riders themselves to navigate the best route, all of which were based on experience. This directly leads to inefficiency. In many cases, the riders’ detours will cause order timeouts, which will ultimately lead to revenue losses for the platform.

The “super brain” algorithm plays the role of the dispatcher, they act as mediators between the customers and the riders. Algorithms take the location of the order it receives, the GPS location of all riders within range, traffic conditions, and even weather as variables to calculate the best option and let the rider closest take the order to optimize efficiency (Figure 3, Zhang, 2025).

However, as delivery efficiency improves, riders are gradually caught up in the endless pursuit of speed and efficiency. Many riders find that as the number of delivered orders increases, the time left for them to deliver becomes shorter. Once the algorithm finds that most people can complete the order within the specified time, it will further compress the order time to improve efficiency.

In addition, Meituan has also introduced a gamified competition mechanism, such as giving riders different star ratings according to the number of orders completed, and they may eventually receive additional rewards to increase their work enthusiasm (Figure 4, Zhang, 2025).

At this point, the algorithm has completely turned riders into food delivery machines. Riders are under tremendous pressure, and they do not hesitate to break traffic rules and risk their lives to shuttle through traffic. Because their salary is calculated based on delivered orders, once an order is overdue, their efforts on this order will be in vain.

Some people may ask, why don’t they just quit? In fact, due to the difficulty in finding employment, many riders have to continue working even under great pressure, even if they quit, they may not be able to find a better job. As a result, despite their enormous efforts and sacrifices, the riders are not getting the compensation they deserve. “They (platforms) don’t worry about no one coming to do the delivery. If you don’t do it, there are plenty of people who will do it,” A rider said (CLB, 2023).

Customer reviews are also particularly important to riders. If a customer complains about a long delivery time, the rider may be fined 200-1000 yuan, which may be several days’ salary for them.

As a result, because they can only earn an average of 3 to 5 yuan per order, most riders have no choice but to work 10 to 15 hours a day to guarantee a monthly salary of 6,000 to 8,000 yuan (CNN, 2024).

The riders race against time, running through every city’s corner. However, the competition among riders only makes it increasingly difficult to complete orders within the specified time and leads to greater pressure.

Algorithms Governance: A dual-edged sword

Algorithm governance means data is processed and interpreted by algorithms, and this often leads to the shaping of individual choices (Flew, 2021). In this case study of Meituan delivery riders, algorithms dominate almost everything. The algorithms use machine learning to optimize the delivery efficiency, and then maximize the revenue, which is its only ultimate goal.

The rider is just one of the many variables the algorithms consider. To increase their income and platform evaluation, the riders have to shape themselves into a delivery machine that complies with the algorithm.

In this process, the Meituan “super brain” algorithms use two kinds of algorithmic control methods: constrained algorithmic control and incentive algorithmic control (Zhao et al., 2025).

Constrained algorithmic control is the rules and regulations that the riders have to follow. For Meituan, it includes the riders monitoring and task assignment. To get paid, the riders follow these rules, they are monitored by the platform’s GPS tracking, facial recognition, and motion sensors to ensure they are on the best route to their destination.

Incentive algorithmic control works as the riders’ candy bar, Because riders are controlled by algorithms like delivery machines for the whole time, they will inevitably feel physically and mentally exhausted. The algorithm gives the riders corresponding rewards by counting the rider’s past performance, including the number of orders completed, customer feedback, and order punctuality rate. The platform gamifies the rewards and turns them into a ranking visible to riders to stimulate their competitive spirit (Zhao et al., 2025).

Surveillance capitalism made Meituan’s success

The platform economy’s success was based on the development of online platforms and multiple types of algorithms. Surveillance capitalism is, without a doubt, based on surveillance of the platform’s user activities. Through machine learning, platform algorithms can quickly understand users’ behavior patterns and needs and provide the required services (Flew, 2021).

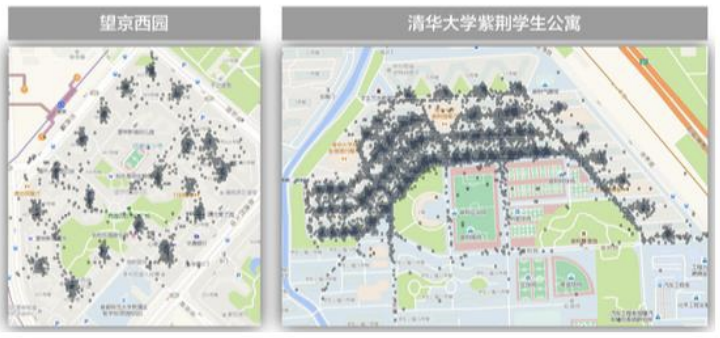

As of Meituan, the riders no longer have privacy when they click to agree to the privacy terms, at least during their work. The algorithm tracks the real-time location information of the riders and their movement status to update the latest status of the order for customers and restaurants. After thousands of trainings, the algorithm can even improve its restaurant advertising push by analyzing the most frequent delivery addresses (Figure 5, Zhang, 2025).

The principle of surveillance capitalism is the maximization of profit, for Meituan, it means attracting more customers to place orders on its app. Customers come first is Meituan’s creed, while the rights of riders seem less important.

That’s explained why the “Clever Hans” myth is a misunderstanding of AI and algorithms. Algorithms have a political, or capitalist nature, it exists to pursue the interests of the companies or governments, how algorithms are used is also determined by companies and governments (Crawford, 2021).

In the 1980s, there was a popular slogan in China: time is money, efficiency is life (China Daily, 2023). In pursuit of higher efficiency and profits, companies used algorithms as a powerful tool, to exploit the weak, in this case, Meituan’s riders, exacerbating social injustice.

Is Meituan wrong in pursuing higher efficiency and profits? No, it is the nature of a company to pursue profits. The algorithm itself does not seem to be wrong either, it was developed only as an efficiency tool. Meituan’s problems can only be caused by China’s lack of effective algorithms supervision.

Algorithms as a black box

The black box metaphor of algorithms reveals how companies use algorithms to obtain user privacy information, maximize profits, and avoid corresponding legal and ethical responsibilities (Pasquale, 2015).

For Meituan, the “super brain” algorithm is the core secret of its profitability. Many new riders waste their time or even suffer penalties because they do not understand the operating mechanism of the algorithm.

The opacity of algorithms and information asymmetry between the platform and the riders are the key problems. The algorithm is like a black box and is completely opaque to the riders. The riders are responsible for accepting orders, and the algorithm is responsible for route planning and acting as an intermediary, but the riders have no idea why they are asked to do so.

In this regard, many experienced riders will take the initiative to share their experiences with novices, teaching them how to use algorithms and analyze new changes in the platform to make it most beneficial to them.

The information asymmetry means Meituan always gets everything in control, they know much more about the riders. For example, riders in Shanwei, Guangdong, began striking in April 2023 because Meituan canceled bad weather subsidies and reduced revenue per order. However, Meituan transferred a large number of riders from other cities to fill the vacancies and paid these riders twice the average salary, with no penalty for complaints, even taking care of these riders’ meals and accommodation (CLB, 2023).

In this way, Meituan used asymmetric information and the majority of riders’ pursuit of salary to resolve the strike. However, it was widely criticized by the public. Indeed, as a company, this approach has completely deviated from social ethics.

Meituan never tells riders which of their private information is used for machine learning. Most riders have no basic understanding of privacy, and 50% of riders don’t even know they have no labor contract with the platform (CLB, 2023). Even if riders realize that their privacy has been violated, they have no choice, and Meituan does not have to bear any legal risks.

What should be done in the future?

The various problems with the algorithms mentioned above are not unique to China. For example, the German online delivery platform started in 2014, and German riders were also confused by the opacity of the algorithm. Similarly, they also formed a mutual help organization to fight against the algorithm (Heiland, 2025).

The difference is that the Chinese government lacks supervision over the algorithms of food delivery platforms. Meanwhile, society knows little about the rights and interests of food delivery riders. Most people are enjoying the convenience of eating affordable food without leaving home while ignoring these riders who sacrifice their interests, even their lives.

The government’s responsibility is the most critical. First, China needs to legislate to require platforms to publish the operating logic and rules of their algorithms. The government can learn from the European GDPR and the Algorithm Accountability Act to limit the algorithms’ exploitation of riders.

Secondly, platforms must establish a mechanism to protect the rights and interests of riders, such as ensuring a labor relationship between the platform and riders, and the platform should be responsible for the riders’ insurance and medical care.

An effective union composed of riders is also necessary. Since most riders are part-time, they need a reliable organization to help them. Guaranteeing freedom of speech and the press is an important prerequisite for ensuring the effectiveness of trade unions.

Finally, it is crucial to raise the public’s awareness of privacy protection for algorithms. Many people think they are beneficiaries of algorithms and enjoy the convenience brought by algorithms, but they are completely unaware that they have already become prey to algorithms.

Final thoughts

There is nothing wrong with the algorithm itself. It is undoubtedly one of the greatest inventions of mankind. However, how to use warm humanity to transform cold 0s and 1s into something that is beneficial to everyone is worth all of us thinking about. When people eat the hot meals delivered by the riders, are they grateful for those riders under the governance of algorithms?

References:

Flew, Terry. (2021). Regulating Platforms. Cambridge: Polity Press, pp. 79-86.

Crawford, Kate (2021) The Atlas of AI: Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, pp. 1-21.

Pasquale, F. (2015). The black box society: the secret algorithms that control money and information. Harvard University Press.

Zhao, H., Yuan, B., Gong, Y., & Liao, Y. (2025). Platform algorithmic control and work outcomes of food delivery employees. The Service Industries Journal, 1–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2025.2477454

Zhang, J. (2025). Combatting the Algorithms: How Chinese Delivery Riders Survive and Thrive in the Platform Economy (B.A. report). University of Chicago. https://doi.org/10.6082/uchicago.14663

China Labour Bulletin. (2023). Food Delivery Industry Research Report (外卖行业研究报告2023). Retrieved from https://clb.org.hk/sites/default/files/2023-05/%E5%A4%96%E5%8D%96%E8%A1%8C%E4%B8%9A%E7%A0%94%E7%A9%B6%E6%8A%A5%E5%91%8ACLB20230511.pdf

Heiland, H. (2025) The social construction of algorithms: a reassessment of algorithmic management in food delivery gig work. New Technology, Work and Employment, 40, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/ntwe.12282

Xinhua. (2025, January 20). Rise of food delivery empire. China Daily. Retrieved from https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202501/20/WS678db4e3a310a2ab06ea803f.html

Lau, C., Stewart, M., & Zhou, M. (2024, October 18). ‘Really squeezed’: Why drivers in the world’s largest food delivery market are having meltdowns. CNN. Retrieved from https://edition.cnn.com/2024/10/17/business/china-food-delivery-drivers-meltdowns-intl-hnk/index.html

Meng, W. (2023, December 6). Breaking barriers, building bridges. China Daily. https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202312/06/WS656fbf1ea31090682a5f19e1.html

Jenny Feng. (2023, April 27). Meituan couriers go on strike in Shanwei. The China Project. https://thechinaproject.com/2023/04/27/meituan-couriers-go-on-strike-in-shanwei/

European Union. (2018). General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). https://gdpr-info.eu/

US Congress. (2023). Algorithmic Accountability Act of 2023. https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/senate-bill/2892

Be the first to comment