A Global Personal Data Defence War Against Cross-Border Crime

When scams became a huge industry, and most people believed their information might be misused, it was time to take action to win the global personal data defence war.

On November 5, 2024, I walked out of Sydney’s Fisher Library, my mind cluttered with the next meeting, when my phone buzzed. A Vodafone customer service agent recited my date of birth, passport number, and the exact date I’d activated my new SIM card—details only my telecom provider knows. “Your number is linked to fraudulent activities” they said, their tone rehearsed but urgent. Within minutes, the call was transferred to “Beijing Police” who threatened incarceration unless I paid nearly 50,000 AUD into Hong Kong bank accounts.

They monitored me via video call 24 hours a day for a month. They weaponized my own identity against me, exploiting every detail: my student ID, my resume, my Chinese ID, my home address. I didn’t realise it was a scam until I called the real Beijing Police and confirmed I had been trapped in the scam for 4 months. The money had vanished into a labyrinth of offshore accounts. At the Newtown police station, the officer’s sympathy felt hollow: “I’m sorry, but there’s nothing we can do.”

This wasn’t just my story.

When I finally mustered the courage to search “Australian scam” on the Chinese social media platform RedNote, thousands of voices echoed my trauma. “I went to the Chinese Embassy to confirm related information, but the worker there didn’t respond to me effectively, and I turned to the fraud team again.” A Chinese student in the US said. This is just one type of scam; Australians lost 2.03 billion Australian dollars last year. Most of them begin with a strange phone call or email. We’re casualties in a silent war where personal data is both ammunition and collateral.

The Personal Black Market: Cost of Identity

Screenshot from Pew Research Centre: Americans are concerned about the use of their data

I believe my information was leaked, just like 81% of Americans who are concerned about how companies use their data and 71% who are concerned about the government, according to the Pew Research Centre’s data.

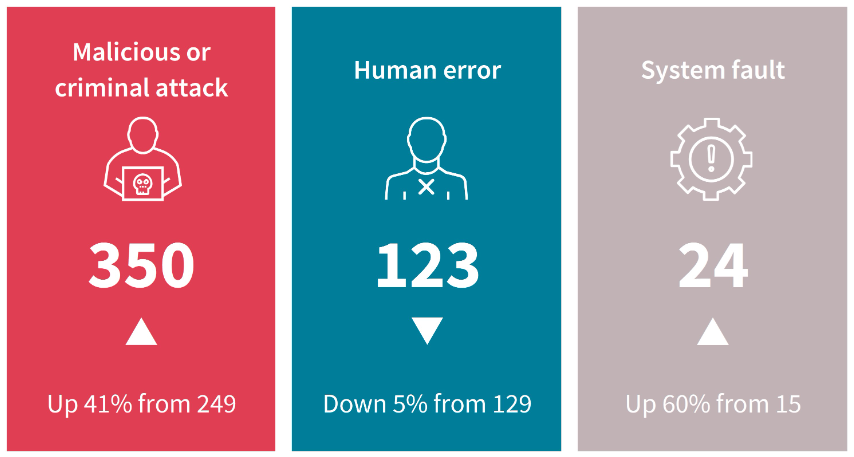

We can feel it. In the second half of 2022, the Australian Information Commissioner estimated that between 1 million and 10 million Australians had their personal information compromised. Shockingly, criminal attacks were responsible for three-quarters of these breaches.

E-commerce platforms, social media networks, websites, hackers, governments, banks, law enforcement agencies, and other institutions are all potential sources of information leaks.

ABC News: Three common reasons for information leakage in corporate

Telecommunications companies are important targets of criminal teams; for example, in 2022, Telstra accidentally published thousands of customers’ details online. Similarly, Vodafone faced a major customer data breach in 2011 due to weak cybersecurity measures, and Optus suffered a devastating attack in 2022 that exposed the data of 10 million customers to hackers.

Geekflare’s blog reported the prices of personal information on the dark web:

U.S. ID: $100

Australian ID: $20

Gmail account: $80

Credit card (up to 5,000 balance): $240

And then, where does the information go?

The criminal team, the buyers of personal information, will transform the data into profits. Steal the money directly if the ID works, or use it as a useful tool of scam, which always happens in places that lack governance like the border of Thailand and Myanmar.

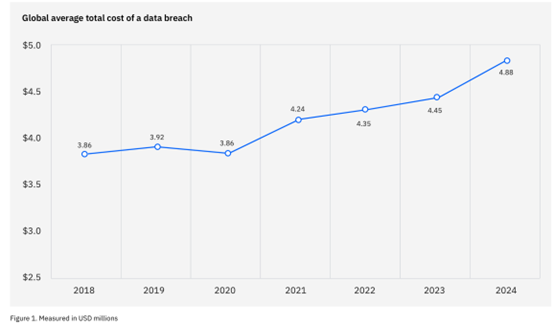

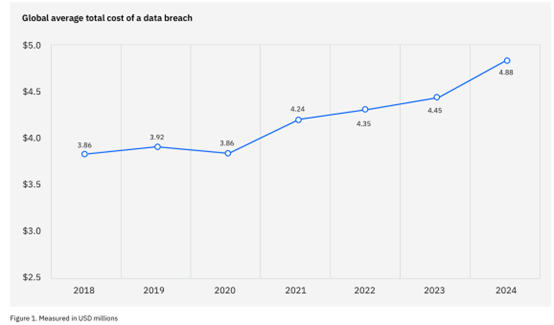

Personal information seems like part of our life; it means a lot but hardly ever has a price. But once it is in criminal teams’ hands, it costs much more than we think. According to the IBM cost of a data breach report, we paid an average of 4.88 million USD last year for each data breach. The business would lose their customers, and individuals would pick up hundreds of scams or spam phone calls, but the biggest challenge is to sentence the criminal team.

Screenshot from IBM cost of a data breach report,2024 : Average cost of a data breach from 2018 to 2024

Legal Labyrinth: When Borders Shield Criminals

After about 200 days, when victims finally realise their data was stolen and seek legal assistance, they confront a fragmented truth. Money flows to offshore accounts, suspects hide behind anonymous tech platforms, and victims’ pleas are trapped in jurisdictional limbo. Like my case, the result is often a dead end—a maze of borders where justice evaporates.

MTTI = Mean Time to Identify; MTTC = Mean Time to Contain

Screenshot from IBM cost of a data breach report,2024: Time to identify and contain a data breach

This does not mean the information leakage or related criminal is out of law. Instead, the UN Trade and Development department points out that 137 out of 194 countries legislated to secure the protection of data and privacy.

However, geographical separation has created gaps between different countries in terms of legal provisions and enforcement.

The first gap is cross-border communication.

When I realised that I was scammed and went to the Police station at 6 am after staying awake all night, I used my broken English described my experience to the Police officer, she looked at me with sympathy, and said “I am sorry to hear that but I could do nothing for you.”

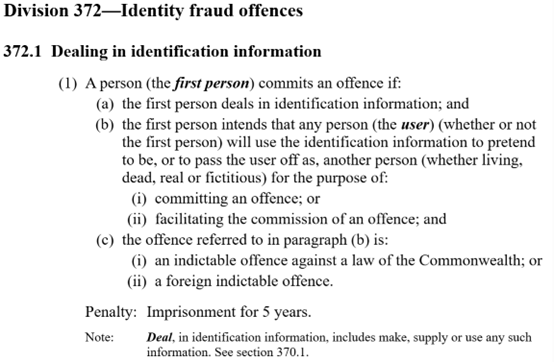

When the information leakage does not incur direct economic losses, it’s illegal, but most of the time, the Police only regard it as a potential risk. In Criminal Code 1995, the data breach is close to the description in Division 372 Identity fraud offences; if a person deals in identification information and has the intention to use it for offence, it breaches Commonwealth law or foreign indictable offence. The penalty could be 5 years. But if we just picked up a scam or spam phone call, most people would ignore it if it didn’t cause any loss.

Screenshot of Criminal Code Act 1995 Division 372, 372.1

But they should act if the victim has a reasonable request. Australian Criminal Code Act 1995 latest version,15.1 Extended geographical jurisdiction—category A, “If a law of the Commonwealth provides that this section applies to a particular offence, a person does not commit the offence unless: the conduct constituting the alleged offence occurs: wholly or partly in Australia”. The information leakage has occurred in Australia, and the Police should find the suspect.

She said the result does not happen in Australia, and from her personal experience, most of the time, the criminal team is in Southeast Asia countries, which means even though they found out who did that, she still could not catch the person directly. Because they are in another country.

That’s why the problem is complex.

Theoretically, the penalty for information leakage is 5 years, reaching the definition of “Serious Crime” in the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime. Once the information has crossed the border, it meets the Article 3 Scope of application under the former framework. Article 18 Mutual legal assistance advocates cooperation between countries, but it also says mutual legal assistance may be refused “if the requested State Party considers that execution of the request is likely to prejudice its sovereignty, security, order public or other essential interests”.

Practically, the legal system between countries might affect the recognition of crime, which might not be regarded as double criminality in both countries. Then, the challenges of language and cultural barriers, diplomatic and political challenges and potential technological constraints, and communication costs, all of them could be the last straw to catch the suspect. It also needs time. Mutual Legal Assistance treaties move at glacial speed—requests take 10–24 months to process (Attorney-General’s Department, 2023). It only takes no more than 10 minutes to check all the details of bank and transfer money to another account, after 10-24 months request and waiting, lost money might have already become white dollars for months.

The second barrier is the information asymmetry between the legal system and the companies.

Finally, I persuaded another officer to help me write a report. He informed me that he sent the inquiry to the Skype team for the ID of the criminal team, but it might take 6 weeks or more to get feedback from them.

My HSBC bank account was under review, and it has the direct information and evidence about my case. What desperate me most is that they are one of the banks chosen by fraud teams. The bank knew how they used the weakness of the bank and similar cases, but they didn’t remind me effectively or report to the police.

During this period, the back office did some operations in my bank account without my permission. At that moment, I called the police and the bank, they just don’t want to talk to each other directly. The officer said, “This is my phone number. Please let the bank call me.” The Bank said your officer will contact us if he needs relevant information. I didn’t know did they contacted each other later, but they played the ball and left the victim to be the audience.

When the information was spread all around the world, the police still hesitated about starting a cross-border cooperation process and waited for the feedback from relevant institutes; the bank is still left victim aside and acted without notice. Personal information, perhaps, was known to more buyers in the global personal information market during this period.

My phone was always called by scammers or spammers from strangers all around the world. Even though I stopped Vodafone’s service, it’s still ringing.

Every bureau is familiar with this scam pattern, but no one does anything to change it. It’s part of their duty, but no one tries hard to prevent things from happening or protect victims from scams. The scam industry wins. If they keep silent towards this situation, the scam industry will always win.

We can’t stop the information flow globally.

But we can build a global personal data defence to protect people from information leakage.

As a criminal industry, the information black market and related industry is the cancer of the Internet, the enemy of the whole world.

Globally, we need a Digital Geneva Convention.

Just like the Geneva Convention (1949) protected civilians and non-combatants during warfare, when personal information faces a high risk of leakage, Digital Geneva Convention is indeed. We need a global pact modelled on the EU’s GDPR. This would mandate 72-hour breach reporting and empower INTERPOL’s Secure Information Exchange Network (SIENA) to share evidence across borders in real time.

Also, it is necessary to strengthen cross-border cooperation under the guidance of INTERPOL. In the past years, INTERPOL has taken some actions to target growing cyber threats. Operation Storm Makers II was organised by INTERPOL and targeted human trafficking fuelled fraud in Southeast Asia, which is a big criminal group transforming personal information into money. Just like the Assistant Director of Vulnerable Communities at INTERPOL, Rosemary Nalubega, said,

“Only concerted global action can truly address the globalization of this crime trend.”

We hope that under the guidance of INTERPOL, more action towards information crime will be attacked effectively.

Locally, Australia should be more sensitive to information leakage.

For the local legal system, CDPR is still a good teacher for legal practice. The GDPR requires companies to invest in their cybersecurity to a minimum level; if they do not, they will be fined up to 2 percent of their worldwide revenue.

A stronger Australian Information Commissioner is vital to preventing information leakage. In 2024, the National Anti-Scam Centre reported $2.03 billion lost to scams across 494,732 cases. However, despite its role in safeguarding personal data under the Privacy Act 1988, the Commissioner handled only 3,215 privacy complaints from 2023 to 2024. As the watchdog for personal information, it must take a more proactive role in combating scams, stopping breaches before data becomes “profitable” for criminals.

Companies handling sensitive data—telcos, banks, social platforms—must consider cybersecurity as a matter of risk management. Manual mistakes could be prevented by training employees to reduce shadow data; cybersecurity design could be upgraded to protect customers from information exposure. At the same time, companies must report suspicious transactions to the Police, rather than just waiting for the Police’s investigation.

As individuals, we have to protect our information. We almost can’t do too much towards passive information leakage, but when other people ask questions about personal ID, verified their personal information first.

It is important to take measures to safeguard personal information. While passive information leaks may be difficult to prevent, verifying the identity of individuals requesting personal details can help reduce risks.

In case of a lost ID, reporting the incident to ID care ensures access to professional assistance. For scams or fraud, notifying local authorities as well as the police where the transaction occurred can be helpful. Demonstrating the connection between information leaks and financial losses may assist in gaining their support. Scamwatch can provide valuable updates on recent scams.

Reference

[1]Flew, T. (2021). Regulating platforms. In *Regulating platforms* (pp. 72–79). Cambridge, UK: Polity.

[2]Australian Government. (1995). Criminal Code Act 1995. Retrieved from https://www.legislation.gov.au/

[3]Guay, J., & Rudnick, L. (2017, June 25). What the Digital Geneva Convention means for the future of humanitarian action. UNHCR Innovation. Retrieved from What the Digital Geneva Convention means for the future of humanitarian action – UNHCR Innovation

[4]United Nations. (2000, November 15). United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crimes (with protocols). Retrieved from United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crimes (with protocols)

AI Acknowledgement

I would like to acknowledge the assistance of Copilot in guiding me to law sources.

As an international student, I am grateful for Google Translate and Grammarly support in translating source material from English into Chinese for easier understanding and refining my grammar and language.

Be the first to comment