Journalism has gone through a massive transformation with the advent of the internet, which has given journalists and publishers new ways of sharing important news and reaching a larger audience. Unfortunately, in recent years, the internet has been a hostile and dangerous place for female journalists. In a new global report released in 2022, 73% of female journalists said they had experienced online violence (ICFJ, 2022). Whether it’s a well-known journalist like Maria Ressa, who even won the Nobel Peace Prize, or an ordinary newspaper reporter, online abuse has been inflicted on these female journalists. This article focuses on another public event – the ongoing online abuse against Taylor Lorenz – as the subject of analysis, reviews the event and disclosure the main factors that led to this situation, while also discussing the role and actions of the platform involved.

Case Review: Taylor Lorenz

Former New York Times journalist Taylor Lorenz has been drowning in online abuse for at least two years.

It all started on International Women’s Day in 2021 when she posted a tweet encouraging people to support women who face online harassment, also mentioning that the harassment and smear campaign she had been dealing with over the past year had destroyed her life (Lorenz, 2021).

However, Taylor Lorenz’s reasonable statement was caught by Fox News host Tucker Carlson, who continued to attack Lorenz herself on his news show, arguing that she was exaggerating, that instead of having her life destroyed, her life was among the best in the country, and belittling her professionalism and talent (The Guardian, 2021). This was only the beginning, of course. Although the journalist’s company, The New York Times, defended her and called Carlson’s attack “calculated and cruel”, it was of no avail (The Guardian, 2021).

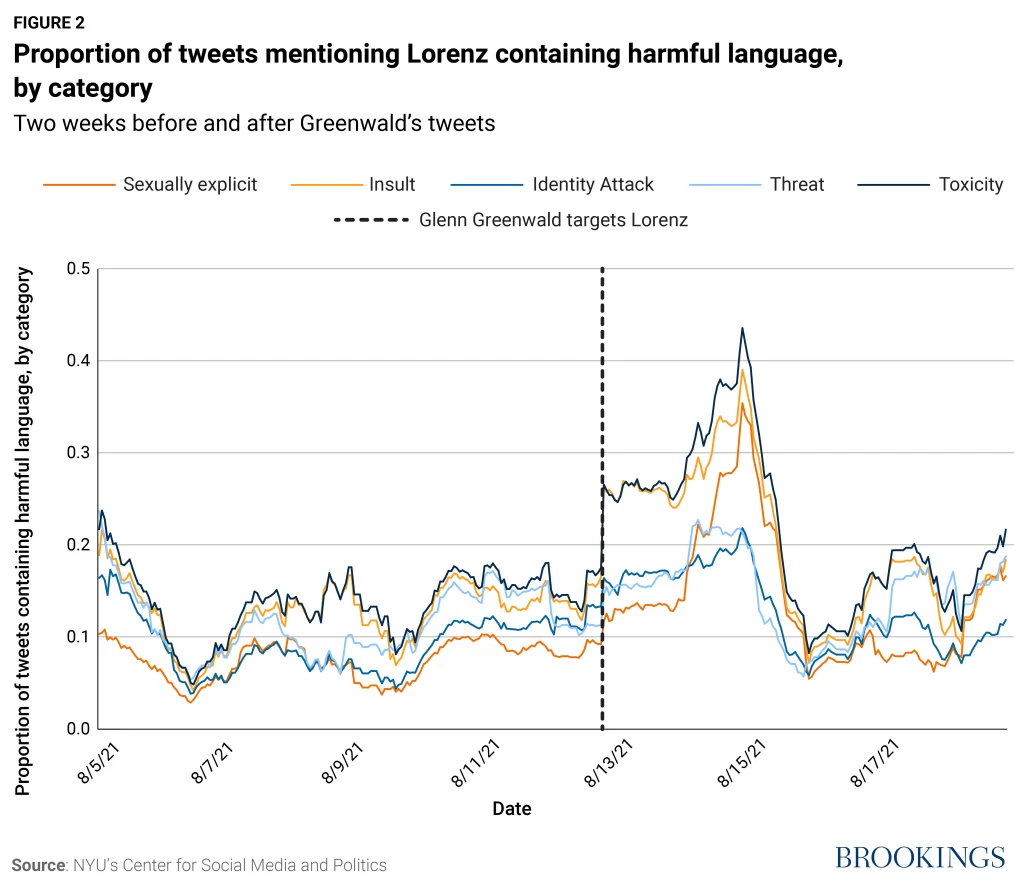

After Carlson’s attack, Taylor Lorenz was subjected to even more violent abuse online, with her social media notifications and messages overflowing with abusive and threatening language. (ICFJ, 2022). Sadly, A study by New York University shows that after being mentioned by Carlson, roughly half of the tweets coming up Lorenz on Twitter consisted of offensive or derogatory comments (Megan et al., 2022). Lorenz said, “The scope of attacks has been unimaginable. There’s no escape” (ICFJ, 2021). In August 2021, another male journalist, Glenn Greenwald, attacked Lorenz again, and two days later, harmful comments about her on Twitter peaked, increasing by 144% (Megan et al., 2022).

Countless death threats were received, trolls not only spreading disinformation about her, which included false claims about her educational background and allegations of stalking teenagers online. “It smears, changing the narrative about you, reframing your stories in a controversial way, that is the really harmful stuff”, Lorenz said (ICFJ, 2022). In an interview with MSNBC, Lorenz confessed that she suffers from PTSD as a result (Richman, 2022).

But the abuse didn’t stop there. Lorenz, who had joined the Washington Post, exposed the creator of an anonymous account called “Libs of TikTok,” In a report published in April 2022, which spread anti-LGBTQ+ views and mocking videos on Twitter. This led to another wave of online violence, with right-wing figures launching sophisticated and vicious attacks against Lorenz, calling her actions doxxing and discrediting her professionalism and identity (Halpet, 2022).

Even now, this abuse continues on a small scale. Twitter Accounts such as @TaylorPostingLs and @TaylorLorenzNOT can be found, posting photos of the journalist being scandalously manipulated, such as replacing her face with a frog, as well as more malicious and abusive language, disinformation, intimidation and denigration.

Why Online Abuse to Female Journalists

It seems that every user of the Internet has his or her own interpretation of this concept, as this phenomenon is not uncommon in the current Internet environment. According to eSafety, online abuse involves behaviour that has a threatening, intimidating, harassing or humiliating affect on a person and can come in some common types including trolling, image-based abuse, sexual extortion, doxing, deepfakes and defamatory comments (eSafety, n.d.). Online abuse that is widely spread and dispersed poses a direct threat to the autonomy, privacy, and dignity of those targeted, changing the way they interact with modern social life, and limiting their full participation (Citron, 2014).

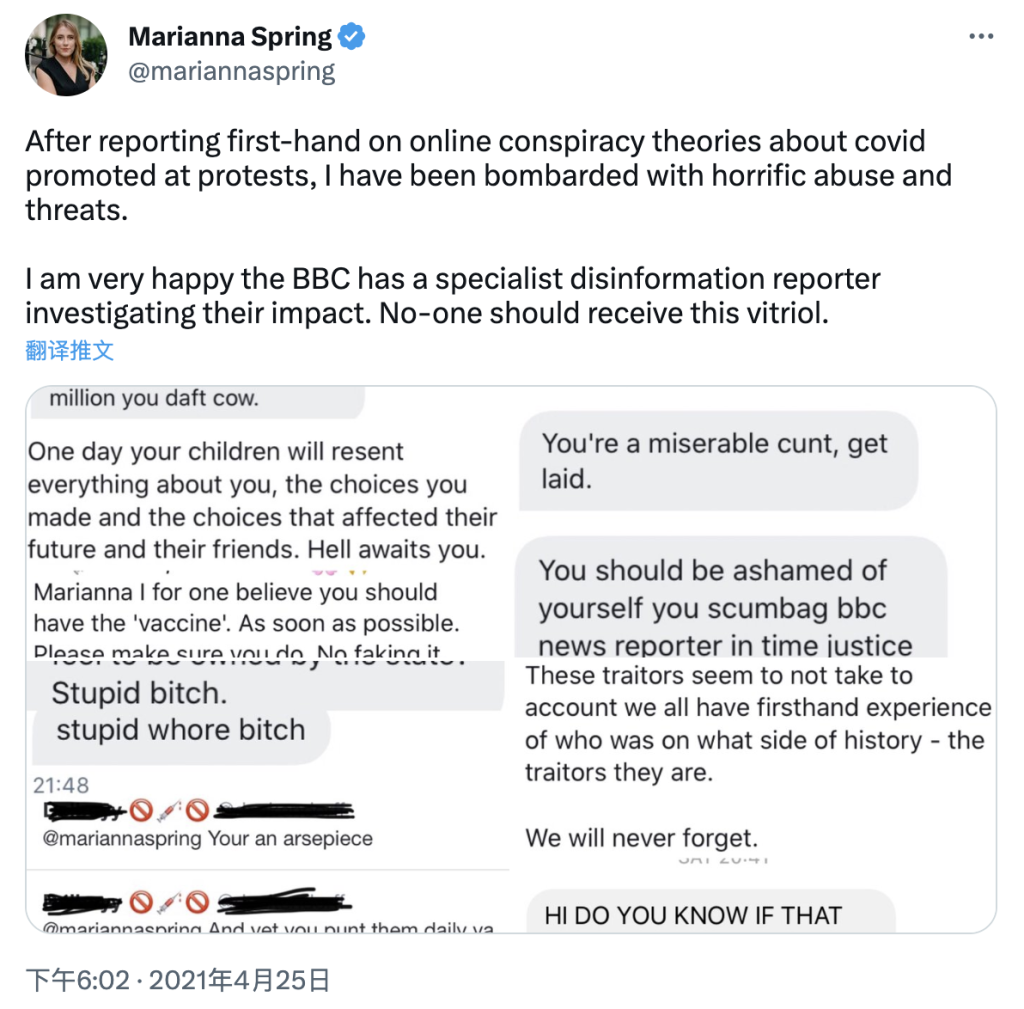

So why is it a group of women journalists who are at the centre of the online abuse storm? Cases abound: Maria Ressa, a CNN journalist of Filipino descent, received numerous death threats and even faced legal charges after reporting on political issues. Twitter Hashtags, #ArrestMariaRessa and #BringHerToTheSenate were created to put her down (Posetti, 2020); Carole Cadwalladr, an acclaimed British journalist who exposed the Facebook-Cambridge Analytica scandal and a series of political scandals, was subsequently the target of a campaign of cyber-violence that was highly gendered (ICFJ, 2022). The Amnesty International report Troll Patrol (2018) on the online abuse of female politicians and journalists on Twitter in the UK and the US revealed that women received 1.1 million abusive or hurtful tweets every 30 seconds in 2017.

Women journalists worldwide face a significant threat from online abuse across various platforms and digital communities. Even with their good qualifications, professional knowledge and excellent work output, they still experience all kinds of attacks from workplace to home. This hate language is abhorrent because it undermines the dignity of the targeted group by promoting distrust and hostility within society. (Flew, 2021). In response to gender, to understand the scope and consequences of online abuse, it is vital to consider abuse and harassment within a broader context of inequality and harm (DeKeseredy, Dragiewicz and Schwartz, 2017). Moreover, the multiple forms of abuse and violence against women are on a continuum, from normalised behaviours such as widespread misogyny and everyday sexism, to criminal or deviant behaviour (Kelly, 2013).

In this context, the discourses that shape online abuse often stigmatise the targeted group by attributing qualities that are commonly seen as highly undesirable, either implicitly As a result of this negative characterization, a negative perception is formed of the group, which is seen as an unwanted presence and a legitimate object of hostility. They are deemed untrustworthy and a potential threat to the stability and welfare of society (Parekh, 2012). “Misogyny and online violence are a real threat to women’s participation in journalism and public communication in the digital age.” (Posseti et al., 2020)

This negativity not only ridicules and denigrates a professional woman, but also undermines the public’s trust in her work and, by extension, in journalism and in the truth. In the case of Taylor Lorenz, it was based on the professionalism and political stance of the woman journalist that the internet spewers, led by Tucker Carlson and Grenn Greenland, as a basis for constantly attacking her reports, opinions and practices, breaking her psyche through disinformation, insulting language and then achieving their own goals.

Challenges of Twitter’s Online Abuse

As it turns out, online abuse is rife on Twitter, even though Twitter’s statement (2019) about online abuse in the Help Center states “You may not share abusive content, harass someone, or encourage other people to do so”. According to Milena Marin, a Senior Advisor for Tactical Research at Amnesty International, Twitter provides an environment where racism, misogyny, and homophobia can thrive without much intervention.

We all know platforms like Twitter highly value freedom of speech as an indispensable expression of freedom of thought (Flew, 2021). Therefore, Twitter can be considered to adopt a more hands-off strategy for moderation compared to various social media platforms (Geiger, 2016).

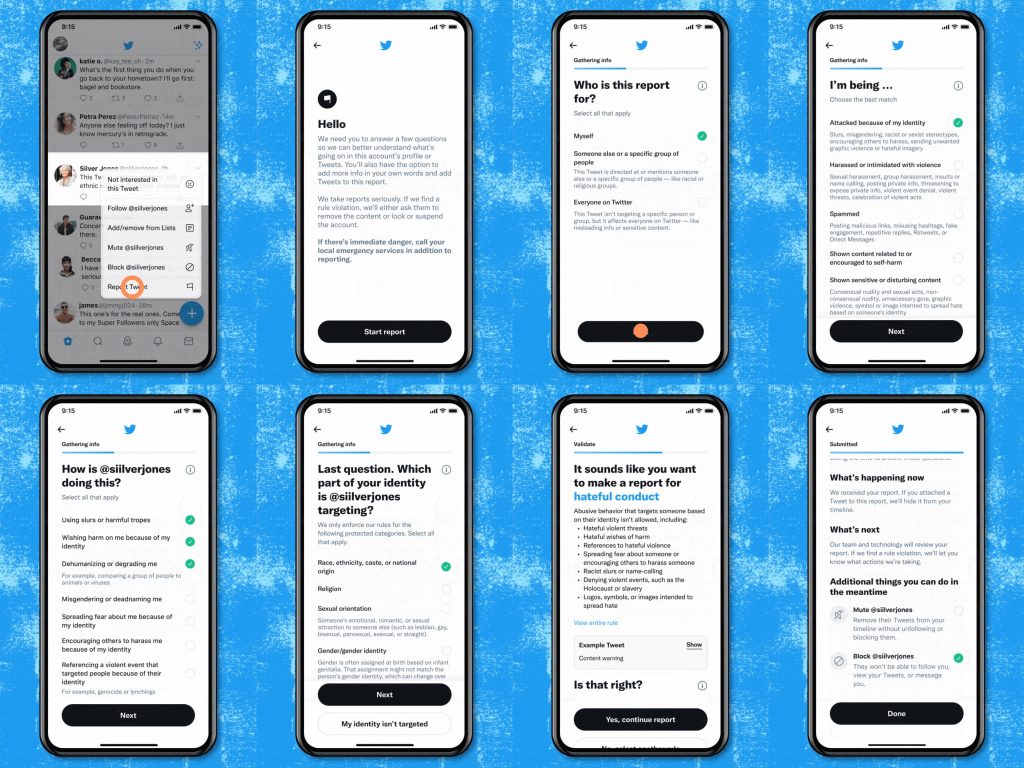

Twitter (n.d.) mainly relies on user reports to detect instances of online abuse, but when celebrities or high-profile individuals are targeted, the volume of abuse can be overwhelming, like a storm, making it challenging to report each instance – and reporting them means looking at the insults, which can be difficult. For instance, Zoe Quinn, the main target of Gamergate which was a campaign of targeted and organized harassment directed towards women (Massanari, 2015) said she has given up reporting on Twitter for a long time (Quiin, 2018). Similarly, Allison Morris, Another UK journalist, said Twitter frustrated her as only two tweets were deleted after 100 reports – one with a threatening message and one with a pornographic image (ICFJ, 2022).

Does a simple ban and deletion of posts work? The fact is that Twitter, as a social platform, allows everyone to have a very large number of accounts because users are not required to authenticate with their real names (Edwards, 2015). This is why Twitter is more prone to online abuse than other social networking sites like Facebook and LinkedIn, which lacks built-in behaviour moderation (Geiger, 2016).

Also frustrating is the chilling effect on women who experience online violence and abuse caused by platform inaction. After the terrible experiences, they often self-censor, do not participate in online discussions, or even avoid online spaces altogether. However, the impact of online violence goes beyond silencing women for fear of being targeted. In many cases, women still continue to express themselves online, but modify their language and actions to conform to societal expectations and norms (Vasudevan, 2023).

These facts exemplify two of Twitter’s shortcomings as a social media platform. First, inaction. Nick Pickles, a representative of Twitter, acknowledged that there is a need for more proactive measures to address the issue of serious threats made against women journalists on the platform (ICFJ, 2022). Secondly, there is a lack of transparency. A lack of transparency exists regarding the measures currently implemented by those big-tech companies to fight online violence. (Dragiewicz et al., 2018), which creates a significant barrier to evaluating how effective their actions are in addressing the issue (Suzor et al., 2019).

In 2018, in response to Amnesty International’s assessment and blame, Twitter stated that they had made changes and taken measures. They claimed to have taken ten times more action against abusive accounts compared to the previous year. Despite this, Amnesty International considers that the measures taken are inadequate to effectively address the extent and type of violence and harassment experienced by women on this platform (Amnesty International, 2018).

The Role of Twitter

Now, a familiar problem lies ahead how to balance two competing principles – on the one hand, promoting freedom of speech and minimising censorship, and on the other hand, implementing effective legal sanctions against hate speech and online abusive behaviour (Flew, 2021)?

There is no doubt that Twitter holds a significant responsibility to address online violence against women journalists and protect their online rights. This requires concrete actions such as providing a safe platform and taking action against perpetrators of online violence. Additionally, Social media companies ought to also update their AI recommendation algorithms, which often promote misogynistic content and groups that exacerbate abusive behaviour (ICFJ, 2021).

In recent years, Twitter has indeed added a number of features to combat online abuse that has been recognised by some women journalists (ICFJ, 2022), also signed a World Wide Web Foundation with Facebook, Google and TikTok in 2021 to address gender-based online abuse(WWWF, 2021). In addition, here are some moderation actions taken by Twitter:

- – Users are allowed to limit non-follower’s ability to reply to tweets and remove followers (Twitter, n.d.).

- – Users can also collect a group of tweets into a single report, providing additional context to mark abusive accounts (Tang, 2016).

- – Twitter enforces its hateful conduct policy to prohibit dehumanizing language and uses human moderators to remove violating content, as well as machine learning tools to detect abusive posts. (ICFJ, 2022)

- – Twitter use nudges to interevent the awareness before online abuse occurred (Common Thread, 2022)

- – Safety Mode: feature auto-blocks accounts to reduce disruptive interactions (Doherty, 2021)

However, platforms still need more work, as they are not only third parties that carry information, but are the foundation of the social media ecosystem. For female journalists, and professional women more generally, to have a guaranteed work experience online, it is necessary to improve the algorithms that promote hatred of women and to continuously enhance the blocking of abusive tweets and replies online. And, we have yet to see trolls punished. Is censoring and banning all there is to it? Perhaps deplatforming is a way, which means to limit all activity of the real people behind the accounts on this platform (Jhaver et al., 2021), as a way to promote a healthy online environment. Furthermore, another crucial requirement is transparency, along with impartially established and assessed standards to gauge the efficacy of measures taken to prevent abuse.

Conclusion

Online Violence is a new front line in journalism safety where female journalists sit at the epicentre of risk (Posseti, 2020). Online abuse against women journalists around the world is highly gendered, posing a threat to their autonomy, privacy and dignity, as well as to the credibility of journalism as a profession. Combating this problem demands proactive solutions, rather than reactive responses (ICFJ, 2022), and it needs to be considered in the broader context of inequality and harm. It is essential for online platforms to acknowledge and take action on this issue in order to ensure a safe and fair online environment.

Reference

Amnesty International. (2018a). Troll Patrol Findings. Amnesty International. https://decoders.amnesty.org/projects/troll-patrol/findings

Amnesty International. (2018b, March 21). Why Twitter is a toxic place for women. Amnesty International. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/research/2018/03/online-violence-against-women-chapter-1-1/

Amnesty International. (2018c, December 18). Amnesty and Element AI release largest ever study into abuse against women on Twitter. Amnesty International. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/press-release/2018/12/crowdsourced-twitter-study-reveals-shocking-scale-of-online-abuse-against-women/

Brown, M. A., Sanderson, Z., & Silva Ortega, M. A. (2022, January 26). Gender-based online violence spikes after prominent media attacks. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/techstream/gender-based-online-violence-spikes-after-prominent-media-attacks/

Butler, J. (2021, March 11). New York Times defends reporter Taylor Lorenz after Tucker Carlson’s attacks. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/media/2021/mar/11/taylor-lorenz-tucker-carlson-new-york-times

Citron, D. K. (2014). Hate crimes in cyberspace. Harvard University Press.

Common Thread. (2022, June 1). How Twitter is nudging users to have healthier conversations. Twitter. https://blog.twitter.com/common-thread/en/topics/stories/2022/how-twitter-is-nudging-users-healthier-conversations

DeKeseredy, W. S., Dragiewicz, M., & Schwartz, M. D. (2017). 6. What Is to Be Done about Separation/Divorce Violence against Women? In Abusive Endings: Separation and Divorce Violence against Women (pp. 141–174). Berkeley: University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780520961159-008

Doherty, J. (2021, November 1). Introducing Safety Mode. Twitter. https://blog.twitter.com/en_us/topics/product/2021/introducing-safety-mode

Dragiewicz, M., Burgess, J., Matamoros-Fernández, A., Salter, M., Suzor, N. P., Woodlock, D., & Harris, B. (2018). Technology facilitated coercive control: domestic violence and the competing roles of digital media platforms. Feminist Media Studies, 18(4), 609–625. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2018.1447341

Edwards, J. (2015, April 18). One statistic shows that Twitter has a fundamental problem Facebook solved years ago. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/statistics-on-twitter-abuse-rape-death-threats-and-trolls-2015-4

eSafety. (n.d.). What is online abuse? ESafety Commissioner. https://www.esafety.gov.au/women/women-in-the-spotlight/online-abuse

Flew, T. (2021). Chapter Four: Digital Platforms and Communications Policy. In Regulating Platforms. Polity Press.

Gabbatt, A. (2021, March 13). Tucker Carlson’s targeting of Taylor Lorenz follows pattern of berating female journalists. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/media/2021/mar/13/tucker-carlson-taylor-lorenz-pattern-berating-female-journalists

Geiger, R. S. (2016). Bot-based collective blocklists in Twitter: the counterpublic moderation of harassment in a networked public space. Information, Communication & Society, 19(6), 787–803. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118x.2016.1153700

Halpert, M. (2022, April 19). Right-Wing Figures Attack Journalist Taylor Lorenz For Revealing Creator Of “Libs Of TikTok.” Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/madelinehalpert/2022/04/19/right-wing-figures-attack-journalist-taylor-lorenz-for-revealing-creator-of-libs-of-tiktok/?sh=1724ccec42d9

International Center for Journalists. (2022). The Chilling: A global study of online violence against women journalists (J. Posetti & N. Shabbir, Eds.). https://www.icfj.org/sites/default/files/2023-02/ICFJ%20Unesco_TheChilling_OnlineViolence.pdf

Jhaver, S., Boylston, C., Yang, D., & Bruckman, A. (2021). Evaluating the Effectiveness of Deplatforming as a Moderation Strategy on Twitter. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 5(CSCW2), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1145/3479525

Kelly, L. (2013). Surviving Sexual Violence. In Google Books. John Wiley & Sons. https://books.google.com.au/books?lr=&id=8cWs45QH-zcC&oi=fnd&pg=PP8&dq=Kelly (Original work published 1988)

Lorenz, T. (2022, April 19). Meet the woman behind Libs of TikTok, secretly fueling the right’s outrage machine. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2022/04/19/libs-of-tiktok-right-wing-media/

Massanari, A. (2016). #Gamergate and The Fappening: How Reddit’s algorithm, governance, and culture support toxic technocultures. New Media & Society, 19(3), 329–346. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444815608807

Nakamura, K. (2021, March 30). Tik Tok, Twitter, and Instagram: Journalists Find Their Footing in a Digital Landscape. Foreign Press Correspondents USA. https://foreignpress.org/news/tik-tok-twitter-and-instagram-journalists-find-their-footing-in-a-digital-landscape

Parekh, B. (2012). Is There a Case for Banning Hate Speech? In M. Herz & P. Molnar (Eds.), The Content and Context of Hate Speech (pp. 37–56). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9781139042871.006

Posetti, J. (2020a, July 1). Journalists like Maria Ressa face death threats and jail for doing their jobs. Facebook must take its share of the blame. CNN. https://edition.cnn.com/2020/06/30/opinions/maria-ressa-facebook-intl-hnk/index.html

Posetti, J. (2020b, September 24). Online Violence: The New Front Line for Women Journalists*. International Center for Journalists. https://www.icfj.org/news/online-violence-new-front-line-women-journalists

Posetti, J., Harrison, J., & Waisbord, S. (2020, November 25). Online attacks on female journalists are increasingly spilling into the “real world” – new research. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/online-attacks-on-female-journalists-are-increasingly-spilling-into-the-real-world-new-research-150791

Quinn, Z. (2018, March 21). Zoe Quinn: Violence Against Women Online. Amnesty International. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2018/03/zoe-quinn-online-violence-against-women/

Richman, J. (2022, April 1). Taylor Lorenz Breaks Down on MSNBC Sharing Experience Being Targeted Online, Contemplated Suicide. Mediaite. https://www.mediaite.com/tv/taylor-lorenz-breaks-down-on-msnbc-sharing-experience-being-targeted-online-contemplated-suicide/

Suzor, N. P., West, S. M., Quodling, A., & York, J. (2019). What Do We Mean When We Talk About Transparency? Toward Meaningful Transparency in Commercial Content Moderation. International Journal of Communication, 13(0), 18. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/9736/2610

Tang, H. (2016, April 25). Report multiple Tweets in a single report. Twitter. https://blog.twitter.com/en_us/a/2016/report-multiple-tweets-in-a-single-report

Twitter Help Center. (n.d.-a). How to control your Twitter experience. Twitter. https://help.twitter.com/en/safety-and-security/control-your-twitter-experience

Twitter Help Center. (n.d.-b). Report abusive behavior. Twitter. https://help.twitter.com/en/safety-and-security/report-abusive-behavior

Twitter Help Center. (2019). Abusive behavior. Twitter. https://help.twitter.com/en/rules-and-policies/abusive-behavior

Vasudevan, A. (2023, March 23). Beyond Deterrence: Understanding the Chilling Effects of Technology-Facilitated Gender Based Violence. GenderIT. https://genderit.org/feminist-talk/beyond-deterrence-understanding-chilling-effects-technology-facilitated-gender-based

Web Foundation. (2022, September 20). Progress by social media platforms. World Wide Web Foundation. https://webfoundation.org/2022/09/progress-by-social-media-platforms/

Be the first to comment