Ransack your family photos, raid your sister’s laptop, pillage your secret snapshots. Surrender to the black box where privacy goes to die.

Finding your ‘self’

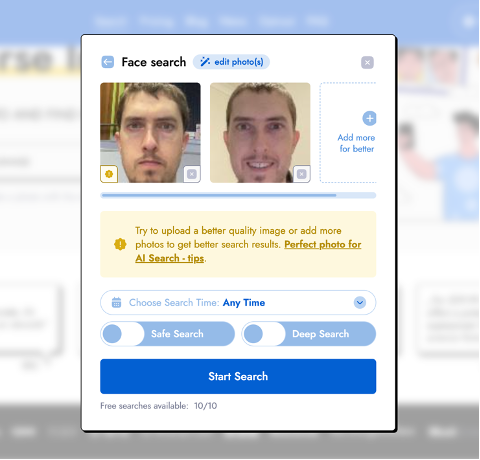

Hovering over the upload button on PimEyes, a face search engine, my cursor might have been trembling a little. ‘Don’t worry’, it assured me.

Click.

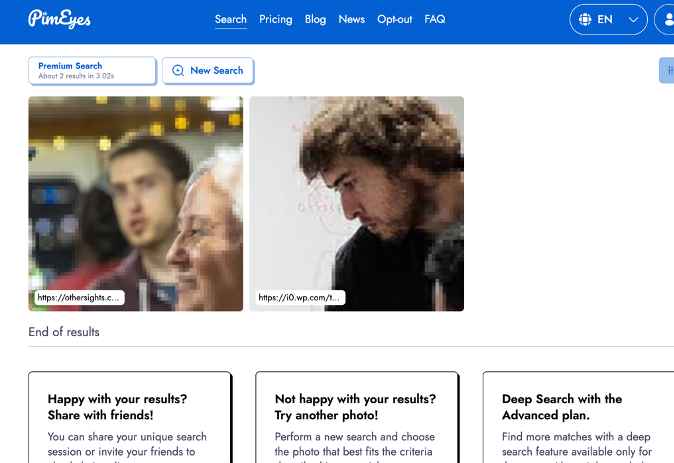

Within seconds, my facial data had swiped left and right with a database of billions to find the perfect match. Here was my result:

That’s me! I could use a haircut in 2017.

The website politely requests that users only search for themselves. So, naturally, I got to work uploading photos of friends, family, strangers, children, dead neighbours…

From Wow! to How?

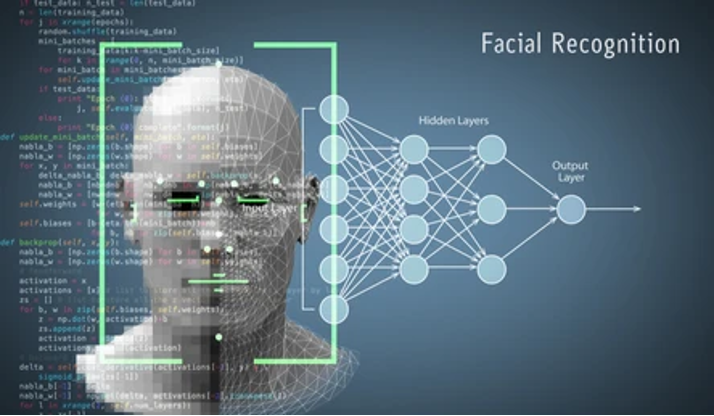

PimEyes works by extracting a contour map of the “spatial and geometric distribution of facial features” (Smith & Miller 2022, p. 168) from photos, which gets converted into a digital template and compared with a massive database: billions of ‘public’ images, indexed and sorted to fuel its machine learning algorithm, a system trained on our biometric data.

I wondered whether I was breaking some sort of law here….

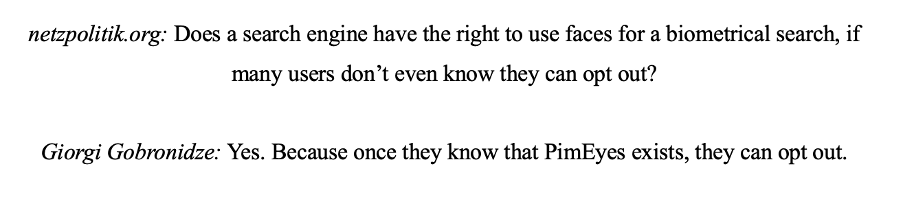

Meet Giorgi

CEO Giorgi Gobronidze has become adept at deflecting responsibility. “We don’t identify people…we identify websites that identify images” (NPR 2023). This is surveillance made simple: stalking love interests, vetting job candidates, trawling for images of children. Any resulting harms are magically insulated by technicality.

Only the most egregious outliers get identified by their security team, such as a single IP address uploading hundreds of images of women. Most objectionable behaviour flies under the radar.

Up for grabs

The company markets itself as a personal privacy protection tool. Paying customers can unlock a range of premium features: access to the hosting URL of image search results, creating alerts for any future facial matches, and assistance from PimEyes ‘agents’ in sending or enforcing takedown requests to website administrators.

But as Terry Flew from the University of Sydney points out, it is “difficult to give informed consent” (2021, p. 77) under the circumstances users find themselves in.

Surveillance by default

In this worryingly amoral response, harvested images are “no longer seen as people’s personal material but merely as infrastructure” (Crawford 2021, p. 16) to support commercial operations, typifying the “extractive” (p. 15) logics of machine learning.

Users in the European Union, for example, are encouraged to upload images of themselves to the service for analysis, including their passport photo page or driver’s ID, simply to exercise their ‘right to be forgotten’ (General Data Protection Regulation) by the company’s data scraping spiders.

This leaves users in a paradoxical bind, with no option to not share their biometrics.

Australia vs. Clearview AI

PimEyes is not the only controversial face search engine.

Back in 2021, the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) investigated Clearview AI, which is marketed towards private companies and law enforcement. Members of the Australian Federal Police were caught experimenting with it.

The Commissioner found breaches of the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth), specifically the Australian Privacy Principles (APPs).

- 3.3: collection, notification and use of sensitive information without consent

- 3.5: collection of personal information to be fair

- 5.2: taking steps to comply with notification requirements

- 10: ensuring the disclosed information was accurate and high quality

- 1.2: implement processes and strategies to ensure compliance with the APPs

The terminology used in these Principles corresponds with public values and expectations.

What do we mean by ‘Privacy’?

The influential explication of the “right to be let alone” (Warren and Brandeis, 1890, p. 195) has framed privacy in terms of the ‘secrecy paradigm’ (Henschke 2017, p. 38), where the moral rights of the individual were expressed in relation to the then-alarming effects of camera technology.

This invention drew attention to information flows across the public/private boundary, spurring the social construction of the privacy norm. This involved demarcating a realm of control and access, physical or informational: the right to exclude unwanted access to, or observation of, the private ‘fortress’.

The metaphor lends itself to evocative language: violations, intrusions, attacks.

The straw man is no island

This “dichotomy of realms” (Nissenbaum 1998, p. 567) is unfortunately not very useful for developing workable solutions. Rather than being an invasion of territory, information collection online has become a “condition of access” (Flew, p. 77).

In her studies of ‘privacy in public’, Helen Nissenbaum argues that defining privacy in terms of a public/private boundary fails to fully account for the dimensions of people’s values or the kinds of harms experienced. Shifting information between intended contexts, aggregating it with other information, and using data processing techniques generates insights and meanings beyond the scope of people’s consent.

Instead, she proposes a standard of “contextual integrity” (p. 581) that might better characterise what people think when they talk about privacy.

A qualified right

Privacy is “inherently social, relational, and contextual” (Bennet 2011, p. 489) – reflecting people’s concerns about how to govern those relationships that constitute social reality, rather than defending the claims of a fictive isolationist.

As a qualified right, claims always compete with the interests of other actors in society to exercise their own rights to conduct activities. For example, police surveillance and public health monitoring have a legitimate social mandate to override individual objections to the collection and analysis of information.

I certainly do not have a warrant to face-stalk my classmates.

Values and harms

The importance of privacy is related to its role in preserving other values: liberty, autonomy, creative expression, free democracy, personal growth, intimate relationships. Some of these derive from the political theory of liberal individualism, while others reflect more communal ideals.

Surveillance can have “chilling effects” (Henschke, p. 41) on the personal and political agency of subjects, the question being one of reasonable use. What kinds of surveillance will society tolerate as legitimate; by who, and for what purposes?

The harms of misuse of facial recognition technology might include threats to personal security, racial and gender discrimination that violates human rights, effects on psychological wellbeing.

“One’s face is a constitutive feature of one’s personal identity” (Smith & Miller 2021, p. 34)

Individuals have distinct rights over biometric data. The Clearview AI case found that facial vector data, even de-identified from the original images, is ‘sensitive information’ precisely because of the “persistent” and “unique” status of the individual’s face (Whitfield-Meehan 2022).

Let’s get ‘personal’

“Society respects people by recognising their will” (Henschke, p. 81)

Henschke (2017) presents a philosophical account of how information might belong to someone.

In one model of property, derived from Locke, the investment of labour or creative energy substantiates the claim. For example, a photographer has certain rights to a studio portrait because they invested the labour in producing it.

Another is relative intimacy to the individual. For any Hegel fans reading, the argument is this: we develop our sense of self-identity through external means, appropriating objects into the project of individuation. These might include things we generate, like love letters or nude selfies, but also information generated about us.

We can be sources – and targets – of information practices. This explains that sense of “alienation” (p. 82) when aspects of ourselves escape our grasp: surveillance footage, leaked documents, false matches or wrongful classification.

Loading you…please wait…

“Assemblages are valuable for the very reasons that their subjects resent them” (Nissenbaum, p. 587)

Datafication and computation complicate social trust, our claims to recognition shattered by the practices of various entities. By organising and connecting data, machine learning systems transform the innocuous into the intimate, inventing new information about people. Considered in terms of “relative aboutness” (Søe et al. 2021, p. 631), anything can potentially become ‘personal’.

Our largely unauthorised, increasingly bloated “data doubles” (Haggerty & Ericson 2017, p. 606) happily provide interested parties with valuable insights about us.

Let’s do it again!

I uploaded a photo of my brother ….and PimEyes found:

Ooh! His boss in a cocktail dress!

Obviously, I searched her face too.

Anyone can play detective against the will of their targets, as verified by my own whimsical mucking around, toying with the “blurring boundaries” (Flew, p. 77) of information, ownership, and ethics.

Building identities

Where was I? Who took those photos? How does it know?

Having my face analysed and seeing candid photos forced me to integrate the search results into my overall life narrative. This “resurfacing [of] past content back to users” (Jacobsen & Beer 2021, p. 2) is significant for identity. It requires a “co-constitution of human and nonhuman sense-making” (Lupton 2018, p. 3), new ways of building understanding.

This mechanism can be empowering, but also oppressive, depending on what kinds of selves get measured and classified. Knowledge about the self is created without necessarily asking for our consent or participation. To some degree, this “undermines the modern project of subjectivity” (Fisher 2022, p. 1320), submitting identity to machinic determination.

Power and control

In a networked control society, we exist as fragments of surveillance – ‘dividuals’ (Deleuze 1992, p. 4). We are our passwords, PIN numbers, fingerprints, database profiles, facial geometry: piecing ourselves together from an array of disparate, modular puzzle pieces.

The owners and operators of the services and technologies distributed in this manner enforce a “powerful governing rationality” (Crawford, p. 17) across society.

“People’s lives are rendered sequential, ordered, and ultimately meaningful and actionable by algorithmic processes” (Jacobsen 2022, p. 1083)

All the better to see you with, my dear!

“To see like an algorithm is not to perceive an image of something or someone, but to produce a world of relations, the grounds from which subjects are made, seen, and named” (Uliasz 2021, 1239)

Challenging ideas about a stable real, algorithms don’t know: they ‘hallucinate’ (Uliasz, p. 1236). From a field of virtual potentiality, the mathematics of ‘neural nets’ produce an outcome whose reasoning is largely inaccessible to us. What is hidden in ‘hidden layers’, is hidden once more by company secrets.

Machine learning is fundamentally human, sharing our biases, a “registry of power” (Crawford, p. 8) optimised to meet certain ends. Privacy offers us “protection against being classified and sorted for organisations’ purposes and goals” (Mai 2016, p. 197)

Limits of individual resistance

The march of technological ‘progress’ and accompanying commodification of personal data is mythologised with an “overwhelming sense of inevitability” (Zuboff 2015, p. 85), resulting in an attitude of “resigned pragmatism” (Hargittai and Marwick 2016, in Afriat et al. 2020, p. 117) by users towards the privacy trade-offs required for digital participation.

This is why imagining privacy beyond the ‘fortress’ metaphor is important. Debates about facial recognition risk, “getting caught up in whether images or templates are personal information” (Andrejevic et al., 2022), which limits the actionable management of powerful organisations, their unjust practices, and harmful user behaviours.

More is at stake than the individual’s right ‘to be let alone’.

Now what?

On March 13, the European Union’s long-anticipated AI Act passed Parliament (Sainsbury, 2024).

Facial recognition and any related biometric data scraping will be banned under most circumstances once the law comes into effect in May, with exemptions for law enforcement.

Unsurprisingly, PimEyes does not meet the law’s standards for compliance. To avoid regulations, the formerly Polish company is today legally based in Belize. This will do little to help it escape the policy instruments being developed globally. Services will need to modify their behaviour if they intend to continue their operations across international markets.

The opaque nature of machine learning, both technologically and institutionally, is an obstacle for regulators tasked with increasing transparency, accountability, and encryption. For instance, Explainable AI (XAI) (Capasso et al. 2023, p. 578) can help make ‘neural nets’ more knowable, minimising discrimination and false positives.

What is Australia doing?

Earlier this year, the Minister for Industry and Science, Ed Husic, released the Government’s interim response to the Safe and Responsible AI in Australia consultation.

In a press release, he stated, “We have heard loud and clear that Australians want stronger guardrails to manage higher-risk AI” (Husic 2024), facial recognition being in this category.

The details remain unclear at this stage, but the national response is likely to mirror the EU AI Act. Other potential avenues include better enforcement of our existing anti-discrimination laws and the Privacy Act 1988, which PimEyes is already in breach of, or perhaps even addressing the absence of federal level ‘Human Rights’ legislation.

The idea that technology has evolved beyond the ability of lawmakers, “their precedents from the 19th century” (Gobronidze 2023, in Tech Times), perpetuates the mythology of AI as ‘ahead’ of society, rather than bound to it. This imagined immunity works on a conceptual level to limit the range of solutions we can pursue, a binary between old and new that echoes the artificial public/private distinction.

PimEyes would have us accept the legitimacy of its own private realm, at the expense of everyone else.

Invisibility cloak

So, what happens if you search Giorgio’s face?

Looks like someone doesn’t like being spied on.

I wonder how long until my account is banned…

References

9 News Australia (2024, January 17). Global calls for more regulations on artificial intelligence | 9 News Australia [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d46CYFyr7qE&ab_channel=9NewsAustralia

Afriat, H., Dvir-Gvirsman, S., Tsuriel, K., & Ivan, L. (2020). “This is capitalism. It is not illegal”: Users’ attitudes toward institutional privacy following the Cambridge Analytica scandal. The Information Society, 37(2), 115-127.

Allyn, B. (2023, October 11). ‘Too dangerous’: Why even Google was afraid to release this technology. NPR. Retrieved April 5, 2024, from https://www.npr.org/2023/10/11/1204822946/facial-recognition-search-engine-ai-pim-eyes-google

Andrejevic, M, Goldenfein, J, Richardson, M. (2022, June 22). Op-ed: Clearview AI facial recognition case highlights need for clarity on law. CHOICE. Retrieved April 5, 2024, from https://www.choice.com.au/consumers-and-data/protecting-your-data/data-laws-and-regulation/articles/clearview-ai-and-privacy-law

Belanger, A. (2023, October 25). Search engine that scans billions of faces tries blocking kids from results. Ars Technica. Retrieved April 5, 2024, from https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2023/10/search-engine-that-scans-billions-of-faces-tries-blocking-kids-from-results/

Bennett, C. J. (2011). In defense of privacy: The concept and the regime. Surveillance & Society, 8(4), 485-496.

Capasso, C., Zingoni, A., Calabro, G., & Sterpa, A. (2023, October). Legal and Technical Answers to Privacy Issues raised by AI-based Facial Recognition Algorithms. In 2023 IEEE International Conference on Metrology for eXtended Reality, Artificial Intelligence and Neural Engineering (MetroXRAINE) (pp. 575-580). IEEE.

Crawford, Kate (2021) The Atlas of AI: Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, pp. 1-21.

Deleuze, G. (1992). Postscript on the Societies of Control. October, 59, 3–7.

Engrish.com (2024) Engrish.com. Retreived April 5, 2025, from https://store.engrish.com/products/all-your-face-are-belong-to-us-face-mask

Fisher, E. (2022). Epistemic media and critical knowledge about the self: Thinking about algorithms with Habermas. Critical Sociology, 48(7-8), 1309-1324.

Flew, Terry (2021) Regulating Platforms. Cambridge: Polity, pp. 79-86.

Haggerty, K. D., & Ericson, R. V. (2017). The surveillant assemblage. Surveillance, crime and social control, 61-78.

Harwell, D. (2022). This facial recognition website can turn anyone into a cop—or a stalker. In Ethics of Data and Analytics (pp. 63-67). Auerbach Publications. Originally published at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2021/05/14/PimEyes-facial-recognition-search-secrecy/

Henschke, A. (2017). Ethics in an age of surveillance: personal information and virtual identities. Cambridge University Press.

Hill, K. (2022). The secretive company that might end privacy as we know it. In Ethics of Data and Analytics (pp. 170-177). Auerbach Publications. Originally published at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/18/technology/clearview-privacy-facial-recognition.html

Husic, E. (2024, January 17). Action to help ensure AI is safe and responsible. Department of Industry, Science and Resources. Retrieved April 5, 2024, from https://www.minister.industry.gov.au/ministers/husic/media-releases/action-help-ensure-ai-safe-and-responsible

Jacobsen, B. N. (2022). Algorithms and the narration of past selves. Information, Communication & Society, 25(8), 1082-1097.

Jacobsen, B. N., & Beer, D. (2021). Quantified Nostalgia: Social Media, Metrics, and Memory. Social Media + Society, 7(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051211008822

Köver, C. (2022, September 8). The user is the stalker, not the search engine. Netzpolitik. Retrieved April 5, 2024, from https://netzpolitik.org/2022/pimeyes-ceo-the-user-is-the-stalker-not-the-search-engine/

KYUP! Project (2023). KYUP! Art Gala 2023. KYUP! Project. Retrieved April 5, 2024, from https://kyupproject.com.au/kyup-art-gala-2023/

Lupton, D. (2018). How do data come to matter? Living and becoming with personal data. Big Data & Society, 5(2), 2053951718786314.

Mai, J. E. (2016). Big data privacy: The datafication of personal information. The Information Society, 32(3), 192-199.

Nissenbaum, H. (1998). Protecting Privacy in an Information Age: The Problem of Privacy in Public, Law and Philosophy, 17, 559-596.

Open AI (2024) DALL-E. https://chat.openai.com/ Images generated: human puzzle assembled by shadowy figures ; EU flag with cybernetic head ; Bart Simpson chalkboard

PimEyes (2024) https://pimeyes.com/en

Privacy Act 1988 (Cth). Schedule 1 – Australian Privacy Principles. https://www.legislation.gov.au/C2004A03712/latest/text

Sainsbury, M. (2024, February 1). EU AI Act: Australian IT Pros Need to Prepare for AI Regulation. Tech Republic. Retrieved April 5, 2024, from https://www.techrepublic.com/article/australia-it-eu-ai-act/

Shutterstock (2024) Ref. #1 https://www.shutterstock.com/image-illustration/network-eyes-surveillance-technology-internet-2284150319 Ref. #2 https://www.shutterstock.com/image-illustration/3d-illustration-facial-recognition-face-detection-1511970647

Smith, M., & Miller, S. (2021). Facial recognition and privacy rights. Biometric Identification, Law and Ethics, 21-38.

Smith, M., & Miller, S. (2022). The ethical application of biometric facial recognition technology. Ai & Society, 37(1), 167-175.

Søe, S. O., Jørgensen, R. F., & Mai, J. E. (2021). What is the ‘personal’in ‘personal information’?. Ethics and Information Technology, 23, 625-633.

Thompson, D. (2023, September 11). Giorgi Gobronidze, Owner of PimEyes, on the Moral Dillemas in Utilitzing AI Technology and How to do It Correctly. Tech Times. Retrieved April 5, 2024, from https://www.techtimes.com/articles/296211/20230911/giorgi-gobronidze-owner-of-pimeyes-on-the-moral-dillemas-in-utilitzing-ai-technology-and-how-to-do-it-correctly.htm

Uliasz, R. (2021). Seeing like an algorithm: operative images and emergent subjects. Ai & Society, 36, 1233-1241.

Warren, S. D., & Brandeis, L. D. (1890). The Right to Privacy. Harvard Law Review, 4(5), 193–220. https://doi.org/10.2307/1321160

Whitfield-Meehan, S. (2022). Privacy: Biometric recognition technology and the’Clearview AI’decision. LSJ: Law Society Journal, (86), 85-87.

Zuboff, S. (2015). Big other: surveillance capitalism and the prospects of an information civilization. Journal of information technology, 30(1), 75-89.

Disclosure: The Open AI ‘DALL-E’ image generating tool was used to create images for the blog post. AI was not used to conduct research or write the article.

Please note: I was having some issues with WordPress’s image caption feature for referencing images, it messed with the formatting in preview mode for some reason. These are included in the Word document uploaded to Canvas! Thank you

Be the first to comment