“It was almost like having an extra teacher in the room, coaching them through the writing process.”

— Salcedo (2023)

Generative AI is no longer a futuristic concept — it has quietly embedded itself into everyday student life. Whether brainstorming ideas, rephrasing sentences, or outlining essays, AI tools like ChatGPT are being used by students and educators alike. The issue, then, is not whether AI should be used, but how it is used — and where we draw the line between assistance and authorship.

As Crawford (2021) reminds us, “AI systems reflect the priorities and perspectives of those who build them, and those who fund them” (p.12). When students rely on these tools to support their academic work, they’re not just interacting with neutral technologies — they’re participating in a broader system of power, pedagogy, and platform governance.

Most universities today do not explicitly prohibit the use of AI. Instead, they caution against mindless dependency. What’s at stake is academic integrity, not technological resistance. The core concern isn’t that students use AI — it’s that they might stop thinking altogether.

This blog post argues that AI-assisted writing is forcing us to re-evaluate what it means to “write,” to “think,” and to “learn.” As authorship becomes increasingly distributed between human and machine, we must rethink academic responsibility and educational values in a world where students might no longer be writing alone.

As featured in a recent GZERO interview with university leaders, generative AI is rapidly reshaping how students learn and how institutions respond.

Mainstreaming AI Writing: How Are Universities Responding?

As generative AI tools become increasingly embedded in student workflows, universities are no longer asking whether students will use them—but rather, how that use should be guided. From brainstorming and outlining to editing and rewriting, tools like ChatGPT and Notion AI have become part of the academic writing routine.

Universities are now shifting from a punitive to a pedagogical approach. As highlighted in a recent Times Higher Education article:

“Educators must create an environment where students feel empowered to use AI ethically, while still learning to write and think critically.”

This statement captures a growing belief in higher education: that AI is not inherently a threat to academic integrity, but rather an opportunity to teach responsible engagement with digital tools.

However, reality presents far more complexity. As noted in the UMass Amherst IDEAS interview:

“AI tools challenge traditional definitions of original thought and authorship in academic settings.”

(UMass, 2024)

With students producing AI-assisted assignments, instructors are left asking: who is the actual author? Are they grading the student’s critical thinking—or the output of a language model?

The policy gap further complicates matters. As summarized in a Ref-N-Write policy roundup, many universities now require students to disclose AI usage in their assignments. Yet, guidelines often remain vague—how much use is too much? When does “assistance” become “misconduct”?

The GZERO video captures this dilemma perfectly:

“We are encouraging students to explore AI, but we’re also struggling to define when that exploration crosses the line into misconduct.”

(GZERO AI, 2023)

This tension—between innovation and integrity, between freedom and regulation—reflects the growing pains of a system adapting to technology faster than its policies can keep up.

In short, universities are now forced to revisit foundational questions:

Is writing still a reflection of student learning?

Or is it becoming a co-produced product shaped by invisible algorithms?

“Am I Still the Author?” — Students and the Blurred Boundaries of AI Assistance

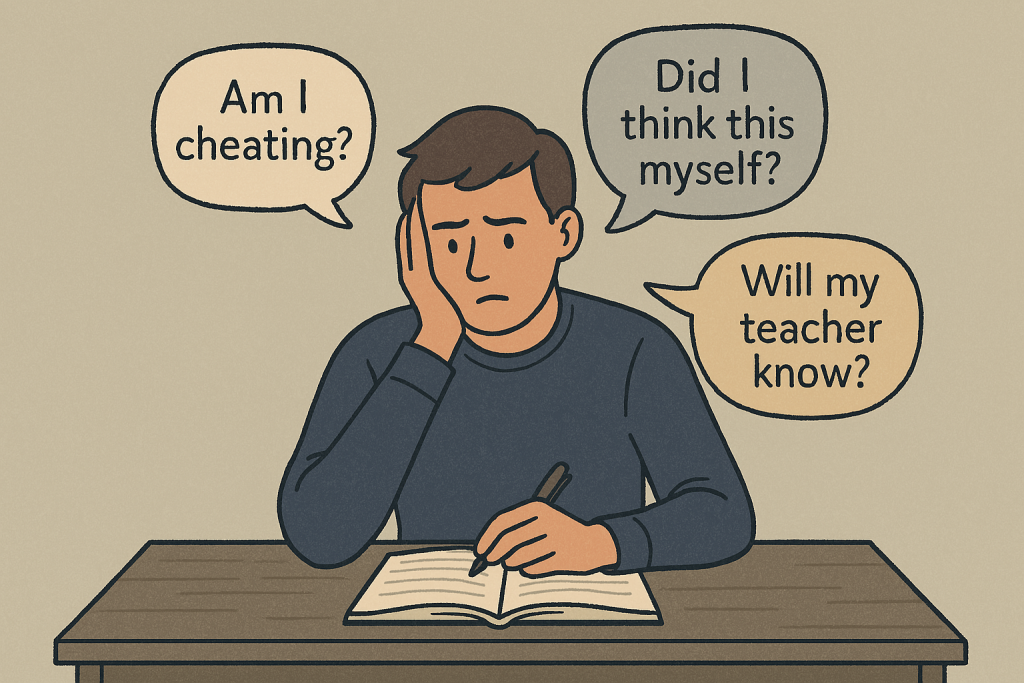

While institutions debate policy and educators design guidelines, students are already facing the ethical and emotional complexities of using AI in their writing. For many, tools like ChatGPT are not shortcuts—they’re collaborators.

Students often describe using AI to brainstorm, paraphrase, or polish their ideas—not to generate full essays. As one student in a Spectrum News interview explains, “It depends on how you use it. It can help you get started, but it doesn’t think for you.” This reflects a common sentiment: the student remains the author, but the process is no longer fully human.

This attitude is also supported by recent student-centered research. A study published in Education Sciences found that most university students used ChatGPT to clarify assignment prompts, generate ideas, or fix grammar—not to cheat (Peters & Gura, 2024). Likewise, a report from Harvard’s Graduate School of Education notes that students prefer to use AI to support their thinking, not to replace it. As one student put it:

“AI should be used to enhance thinking—not replace it.”

(Harvard GSE, 2024)

Yet even when students feel in control, the line between support and substitution isn’t always clear. The fear of “using too much AI” without realizing it—of crossing an invisible line—creates anxiety. They are unsure how much help is acceptable, how much originality is required, or whether instructors can detect and penalize them even when they’ve acted in good faith.

This confusion stems not only from institutional vagueness, but from the nature of AI itself. As Andrejevic (2019) argues, automation replaces human judgment with mechanical calculation, often in ways users don’t fully understand. Students may be choosing words, but the structure, tone, and even rhetorical flow can be subtly shaped by the AI’s algorithmic preferences. The result is a co-produced piece of writing—technically theirs, yet not entirely their own.

These blurred boundaries raise difficult questions:

1. “If the writing sounds smarter, but the thinking hasn’t deepened—has learning really occurred?”

2. “If a student inputs the right prompts, is that academic skill, or system mastery?”

What we’re witnessing is a shift from traditional authorship to distributed authorship, one that challenges not only students’ self-perception, but the very assumptions upon which academic evaluation rests.

Rethinking Academic Governance in the Age of AI

If nearly every student is using generative AI tools in some form, then the question for universities is no longer “Should we allow it?”—but rather, how do we govern it responsibly?

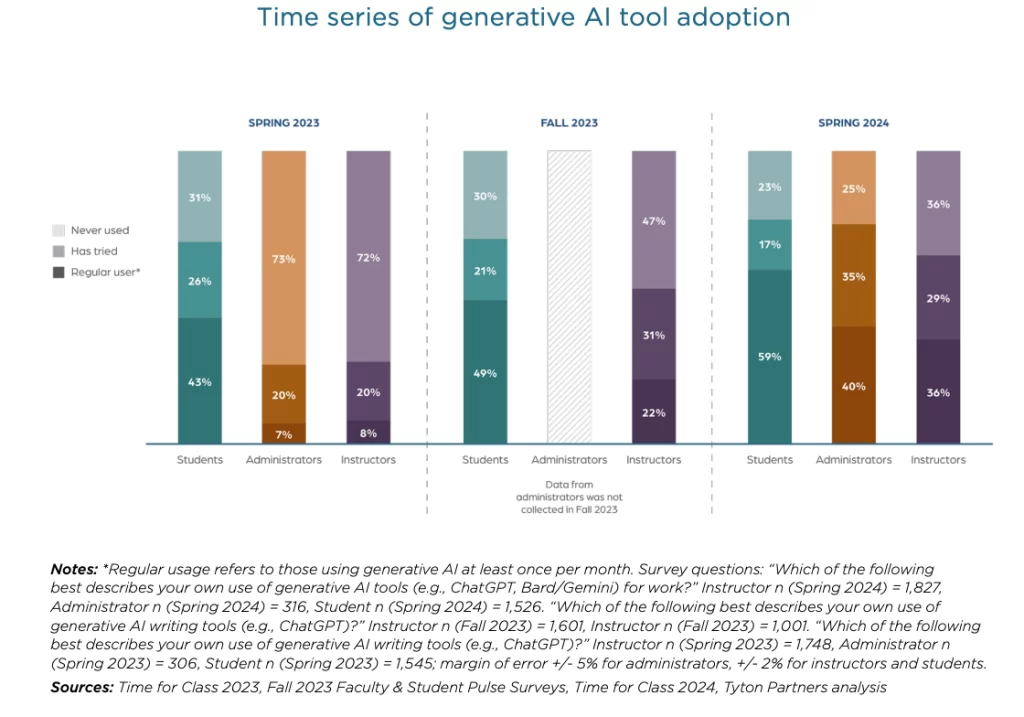

Universities must acknowledge that AI is not inherently a threat to learning. Instead, it offers an opportunity to reimagine authorship, assessment, and digital literacy. As the Time for Class 2024 survey by Tyton Partners shows, nearly 60% of students are now regular users of generative AI tools (defined as monthly or more), while faculty adoption has quadrupled, from 8% to 36% in just one year. Administrators are also catching up, with 40% reporting regular use. AI is not optional anymore—it’s embedded in academic life.

In response, some universities are moving from punitive models to pedagogical policies. Rather than banning AI, they’re introducing “AI usage declarations” in assessments, where students reflect on how they used AI, and justify whether it supported or replaced their thinking. This encourages transparency over fear, and helps educators distinguish genuine learning from passive automation.

Teachers, too, must adjust. Instead of ignoring AI or catching students “cheating,” instructors can guide students in comparing human and AI-generated writing, developing better prompts, and integrating AI in the writing process ethically. The goal is no longer to eliminate AI—but to teach with it.

As AI reshapes cognition and authorship, education must also evolve. This means adopting new assessment models: collaborative writing, process portfolios, and critical reflections, rather than product-focused grading alone. Universities that fail to adapt risk disconnecting from the tools students are already using—and hiding rather than confronting academic dishonesty.

So… if AI helped me write this, am I still the author—or just the project manager?

As generative AI reshapes academic life, universities are facing a pivotal choice: resist, regulate, or reimagine. This blog has shown that the question is not whether students should use AI tools, but how they can do so ethically, reflectively, and responsibly. We’ve seen how teachers, students, and institutions alike are navigating blurred lines between assistance and authorship—and how governance is slowly shifting from prohibition to pedagogy.

But important questions remain: When students rely on AI, are they thinking less—or thinking differently? Can universities adapt fast enough to support meaningful learning in an algorithm-driven world?

In the end, the future of AI in education may not lie in firm boundaries, but in shared accountability—where learning, technology, and authorship are co-developed rather than policed.

References List:

Andrejevic, M. (2019). Automated media. Routledge.

Crawford, K. (2021). Atlas of AI: Power, politics, and the planetary costs of artificial intelligence. Yale University Press.

EdSurge. (2023). How an AI-powered tool accelerated student writing. https://www.edsurge.com/news/2023-05-04-how-an-ai-powered-tool-accelerated-student-writing

GZERO AI. (2023, July 19). ChatGPT on campus: How are universities handling generative AI? [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DKBa4B1XPVE

Harvard Graduate School of Education. (2024). Rethinking AI’s role in student writing. https://www.gse.harvard.edu/news/24/ai-writing

Peters, C., & Gura, M. (2024). Student uses of ChatGPT in academic contexts: Not to cheat, but to clarify. Education Sciences, 14(2), 118. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14020118

Salcedo, A. (2023, June 2). How students use ChatGPT in the classroom. EdSurge. https://www.edsurge.com/news/2023-06-02-how-students-use-chatgpt-in-the-classroom

Spectrum News. (2023, November 20). Students’ perspectives on using AI in schoolwork [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LUogmrqYqak

Times Higher Education. (2024). Artificial Intelligence and Academic Integrity: Striking the Balance. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/campus/artificial-intelligence-and-academic-integrity-striking-balance

Tyton Partners. (2024). Time for Class 2024: Faculty & Student Pulse Surveys. https://tytonpartners.com/timeforclass2024

University of Massachusetts Amherst IDEAS. (2024). Tool or temptation? AI’s impact on academic integrity. https://www.umass.edu/ideas/news/tool-temptation-ais-impact-academic-integrity

Be the first to comment